Volume 3, page 30-39

Page 30

Our Book on Painting conforms to a theatre in which inclination can find its choice. If it favours what is farcical or jolly, it can skip the sad cases. Is it only predisposed to the sad material, it can reject the comical acts, thus overlooking those whose failings have been considered and engraving in memory a fixed recollection of all the commendable scenes.

But those who are curious by nature mirror themselves in both, and already as of old they have kept the deeds of thedeceased as mirrors for the living. One man (says Solomon) is a mirror of another. Thus I believe I have already pleaded sufficiently for my way of writing.

Just now we saw the features of the spectators relax when we brought the farcical life of Jan Steen on the stage, and smirked at the comedy. Now the drawn eyebrows will crease the foreheads at the showing of this following tragedy.

I do not know in what year the unfortunate portrait and history painter JAN LINSEN was born, but only that he lived in Hoorn when he met with the accident (about which we will later report) in 1635. No accident (goes the saying) goes alone. And when a man is born accident prone, one disaster follows on another, like the shadow does a figure.

After he had advanced so far by diligent practice in art that he could (as people say) get by, he went to Rome to continue practicing his art after commendable models.

Page 31

Having embarked for Italy from I do not know where, he was captured as sea by Moors, set on their shore and, plundered mother naked, brought before their leader. But through a rare incident he kept his life and got away, of which events, returned home, he made a painting which is very handsome. Thus writes the painter Johannes Bronckhorst from Hoorn in a letter of 18 May 1718 and also that this work still exists and is to be seen with Mister Adriaen Beverwijck in Hoorn, as are other works worth seeing because of their pleasing way of painting.

Jan Linsen, now to mention his final mishap, sat playing cards in an inn in Hoorn, and being on the winning side, his buddy first begins to grumble at his loss and finally to say: I am going to stick a knife in your skin. This made Jan Linsen laugh, not suspecting any evil, seeing they had always been good friends, and he said: yes stick it up my ass. The other then treacherously gives him a fatal stab under the table. Falling to the ground he said with blanched lips that he has been treacherously murdered by one whom he loved, but that he forgave him, after which he gave up the ghost and thus ended his life unhappily.

Just like a farmer awakened

By care which serves him as alarm clock,

When the time for planting, sewing,

Or mowing the ripe golden yellow grain

Is at hand: he looks to the East,

Page 32

When daylight only just blushes through the night,

To, when the day begins to light up,

Carry out his work with effort:

so I also found myself awakened by care when it was timely and with other painters of the same year, some biographies of their contemporaries had to be added for which the hope of coming by the necessary information repeatedly had me look out with longing until I received light on things that had been wrapped in doubtful obscurity. But just as it often happens that the Eastern horizon, wrapped in heavy vapour, prevents the sun from mirroring itself in the ocean in its time, so it has also happened more than once that the necessary reports, clouded by the passing of time and oblivion, did not appear to us in time to record them. This is the situation with the present biography of Gerard ter Borch II, who should have been placed in the year 1618, have only come into my hands now that we have already moved ahead with printing to the year 1635. It is the same with the birth date of Gabriel Metsu. Of what help was it that we received only too late that which we lacked? But what counsel? Van Mander had to live with it just as do I.

It is not recorded in the biography of Gerard Dou that he had the honour that Charles II, King of England, taking great pleasure in his brushwork, summoned him to his court. But he found reason to refuse this summons because the turbulent court life was not commensurate with his quiet nature or because his friends

Page 33

advised him against it, as appears from the verse below:

How now, Douw! Is Stewart to drag you, the crucible of brushes,

To Whitehall? Aye, go not to Charles' Court

Sell not thy freedom for smoke, for wind, for dust.

He who would seek the favour of princes, must play the part of slave and sycophant.

It would also have been necessary that we employ the verse below to the fame of the man’s art in his biography. In it the poet addressing him says the following upon seeing a portrait by Jan Lievens.

Is this but dead paint, Lievens, how!

Life sparkles in your strokes,

Ay, do not add a single stroke,

Or the portrait might well ask money for sitting,

And swear that the painting.

Is Silvester, and he a copy.

But who alone can know as much as many know combined? It is therefore futile to torture myself about this. Were it otherwise there would have been no opportunity for any delayed stories, which are rather welcome even though untimely, because the reader can link them in his memory with what has been previously mentioned about Gerard Dou and Jan Lievens. But possibly this will be counted (no matter how innocent) as a mistake, as happened to me when writing about Naples in Sicily on page 278, line 1 of my first book,

Page 34

about which a certain observer informed me thus: I have not been able to locate Naples in Sicily, but I have found Neapolis, a part of the old city Syracuse by Cluverus in Sicilia Antiqua, though this is merely a printing error. See how closely people know how to nitpick.

To now continue with Gerard ter Borch II, with whom we have started, he was born in Zwolle in Overijssel in 1608 [= 1618]. The issue of an old respected family and well-raised, he possessed much understanding. Also, the goddess of art already favoured him from an early age. His father [= Gerard ter Borch I], who was a good painter and had practised his art in Rome for many years, was the first teacher of his youth. He later lived with a painter in Haarlem, but what he was called I do not know. But I do know that when he could fly on his own wings, he got the urge to travel, and visited foreign lands, such as Germany, Italy, England, France, Spain and the Netherlands, where he left behind examples of his prowess with the brush on all sides. In 1648 he went to Münster to the peace negotiations, where he first made the acquaintance of the painter to the Count of Pignorando [= Peñeranda]. This man, who had heard by rumour that Ter Borch was a great master artist, was friendly to him, all the more because he was working on a painting for said Count which depicted the Crucifixion of Christ and which he could not resolve to his own satisfaction. So he asked our Ter Borch if he would lend a helping hand with it, which he did. When it was finished he showed it to the count, who was very pleased with it,

Page 35

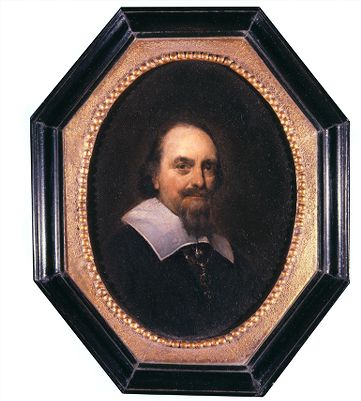

but at the same time reproached him that he had not done it by himself, which he at last admitted. The Count ordered him to bring this master to him, which (under compulsion) he did. Ter Borch was immediately asked if he would paint his portrait, to which he agreed at once, seeing that his fortune stood to be launched [1].

It pleases us to relate an amusing incident between this count and Ter Borch while he was painting his portrait.

Experience has shown to us that some painters had habits while they painted that they could not do without. Johann Wilhelm Baur spoke out loud while painting (not realizing what he was doing) to his subject (even though it was immobile) that he had in front of him to paint from, and funny Bamboccio kept on curling up his moustache while painting. Our Ter Borch whistled a tune with his lips whenever he applied himself to something with concentration. When the Count first sat for him to be painted and he in deep concentration started to whistle a tune according to his old habit, the Count was at first offended by this, as being inappropriate in the presence of so generous a prince, and rose from his seat, to leave. But then Ter Borch, noticing his error, absolved himself by saying that he was used to doing this without realizing it, whenever a painting progressed well and to his satisfaction. At this the Count sat down again and said, laughing: Whistle on, then.

1

Gerard ter Borch (II)

Portrait miniature of Don Caspar de Bracamonte y Guzmán, Conde de Peñeranda (1596-1676), head of the Spanish delegation at the peace negotiations at Münster, c. 1647-1648

Rotterdam, Museum Boijmans Van Beuningen, inv./cat.nr. 2529

Page 36

This portrait, to which he especially applied his energy and which succeeded well, gave him not only the opportunity to paint still more for the Count but also to paint all the ambassadors who had gathered together at the peace negotiations [2-5]. These portraits were praised highly, and each of the Lords and especially said Count, took such pleasure in them that he did not cease to entreat him, with promises of great rewards, to go with him to Spain, which he did. Having arrived there, he painted the portrait of the King [6] and many of the highest at court with great relish. For this reason the King knighted him, and gave him a golden chain and a medallion on which was stamped a portrait of the King, a sword, and a pair of silver spurs. He also painted many of the first ladies in waiting of the court and many other wealthy people who, infatuated by his flattering brush, would have kept him busy there forever. But he did not stay there many years because he knew how to insinuate himself into the favour of the ladies too much to please the Spanish (who are immediately suspicious and competitive in matters of love), so that they would have liked to give him a fig to have him burst. Warned about this, he (so the saying goes) packed his bags at once and departed in all haste from Madrid for England, where he was well-known for his painting and gained much money and favour. When he wanted to ship out for France (knowing that according the laws of England the customs officials guard against the export of money) he hid his gold in his boots, which he had deliberately made muddy and unsightly,

2

Gerard ter Borch (II)

Portrait of Adriaan Pauw (1585-1653), c. 1646

Private collection

3

Gerard ter Borch (II)

Portrait of Adriaan Clant tot Stedum (1599-1665), 1646-1648

Groningen, Groninger Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1964-0265

4

Gerard ter Borch (II)

Portrait of Godard van Reede (1588-1648), c. 1646

Oud-Zuilen, Slot Zuylen, inv./cat.nr. S190

5

Gerard ter Borch (II)

Portrait of Caspar van Kinchot (1622-1650), 1646-1647

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 1050

6

Gerard ter Borch (II)

Portrait of king Philip IV of Spain, between 1637-1640

Private collection

Page 37

so that they would not attract attention. And so he came out of it better than Erasmus of Rotterdam in the days of Henry VIII, because all of his money was taken from him.

In France he painted various portraits of wealthy persons and also a number of cabinet pieces. And having thus been abroad for several years, he arrived back in Overijssel, the land of his birth, and settled down in Deventer, where he married a niece of his but did not have any children by her. Here he gained the respect of all those well-placed by his pleasant behaviour and art and also served on the council of Deventer for many years until death tore him away in the year 1681, the seventy-third of his old age. His body was returned to his native city of Zwolle and buried in state.

In the year 1672, when the city of Deventer was being fortified because of the risk of enemy attack and Willem III Prince of Orange was present there, the burgomasters and councillors sought to obtain a portrait of him in commemoration. The Prince answered them that there was no opportunity for it but that he had been painted by Caspar Netscher and that he would allow them to come and make a replica of it. But they declined the prince’s offer, saying that they already had Netscher’s master at their disposal. His highness agreed to this despite the fact that in those troubled times he could hardly spare a few hours to sit. So Ter Borch had to realize it in his first attempt, while the Prince sat at table, and finish it off afterwards, in his studio. This portrait however was kept so securely by one burgomaster

Page 38

and so tightly locked away that when it was brought to light afterwards, it looked like it had been darkened and was ruined.

Subsequently he was approached to again paint the picture of the Prince, but he demanded that his Highness sit eight hours for it. But this sitting did not go as well as Ter Borch had wanted it to, for which he inventively paid the Prince back, as this story will show.

The Prince went to sit, but because he dreaded the long time, he continually asked the painter about this and that. And knowing that Ter Borch had played the rôle of the adored lover more than a little in Spain, he asked him how many mistresses he might have had in Madrid. He replied, can your Highness tell me how many seas he has crossed? I cannot recall because it is too many, answered the Prince. I can tell you just as little, Terborgh responded, concerning my mistresses.

Later on the Prince brought up something else. It makes the time pass, so the saying goes. Among other things he asked our knight if he had also painted the King of Spain. Yes, he answered, but he did not sit like an idiot. How, said the Prince, do you come to compare the King to an idiot? Well, yes, replied Ter Borch, would it not be idiotic when one wishes to be painted if one would not sit still? The Prince, sensing that this was a double stab, and that the painter was a droll fellow, from then on sat much more still, until he rose, thinking that the agreed-on

Page 39

hours were up. This took place in the house of the chief bailiff Ter Borch, cousin of our painter, who was a man of great understanding, of which the Prince availed himself much and with whom he also stayed when he came to Deventer.

Ter Borch coaxed the Prince to again sit for him one last time, but he would not, saying that the artist would have to come to The Hague. Afraid of losing some of the essence with the final painting (as sometimes happens with frequent over painting), he made an exact copy of the first and took this along to The Hague.

At last the Prince sat for it again and was so pleased with it that he put his own seal on it and ordered it to be mounted at once. Thus our painter (without intending it beforehand) kept the real portrait of the Prince, which he later traded with an Amsterdam gentleman for an open coach, which he has kept for his use ever since.

He knew how to imitate with his brush in a lively way not only the fixed features and the entire elegance but also the clothing and rare fabrics according to their nature. But above all he was able to paint white satin so naturally thin and artful that it truly seemed to be satin, which is why he often used it in his art works.

Especially praised amongst the manifold and elaborate painted portraits is that of Miss. Cornelia Bicker, about which Jan Vos composed this four-line verse: