Volume 1, page 360-369

Page 360

so naturally as if he had such an object as model before him.

He early on headed first for France and then to Rome, where he remained 16 consecutive years, daily striving for the continuation of his art while he was spurred on by the many handsome examples that Rome had at that time. By this activity he finally got so far that he was counted on the list of the most commendable artists and also became beloved by them for his politeness and jokes.

When he was occupied with his work, he was quiet and sat totally enraptured by his thoughts. The reason for this, as I have already begun to tell, was that he did not use life while painting, not even for his figures, but used the concept that he had formed of them. Which is why when his spirits seemed tired by steady thinking, he revived them by playing a happy tune on his violin.

The Romans gave him the nickname Bamboccio, a name used for such people who specialize in the making of Italian jokes, strange kinds of bows and bends of the body, and the making of inventive figures.

Now nature had given him such a form that whoever saw him had to laugh at his misshapen figure, for his lower body was three times bigger than his upper body, he had a very short chest on which the head rested sunk between his shoulders and without neck. In addition he had a jolly and farcical disposition, as we will demonstrate with some instances.

Page 361

It is told that once, as a joke, he dressed up with an apron up to his arm pits, and thus placed himself at the door jamb of a store where much traffic passed, so that the passersby took him for a large baboon, at which he himself had a good laugh. But I think that these must have been bright lights like the ones who passed an apothecary's shop in Amsterdam, where a dressed monkey sat in the window, whom they asked, little man, which way must we go to the town hall?

But a more inventive and believable farce played by him is related by Joachim von Sandrart on page 311 of his Teutsche Academie, where he relates the following (translated into Dutch): Bamboccio was able to collapse his upper body even shorter than normal, so that it seemed when he was dancing that he was only a human lower body on which a head stood, and even so he was so nimble and fast with his long legs that it was no trouble for him to jump over others. It happened one time that he, Nicolas Poussin and Claude Lorrain, and I (says mentioned Sandrart) had come to Tivoli to relax a little, and that he, seeing that there was a rain storm brewing, had left the company in all haste and had driven off without our noticing.

Now as he was a joker by nature, he had leaned forward when he was about to go through the gate of Rome, and pulled the horse blanket over head and humpback, and had thus entered the city in a gallop.

We were therefore a bit at a loss, not knowing where he had gone, and as soon as we arrived at the

Page 362

gate, asked the guard if he had seen someone precede us, to which he answered that he had seen the horse of Viterinno, but mounted only by a covered tote bag, with boots on both sides.

So that when we were come together, none of us could restrain from laughing whenever we thought that he had been taken for a covered bag and had fooled the guard this way. But no matter how farcical and comical he was, the end of his rôle in life will show that the saying of Vosmeer in Vondel's Gysbrecht van Amstel:

I am a Child of Het Gooi, fallen in God's wrath,

Raised in Laren;

can be applied to him.

In the meantime his parents and friends longed to see him once more and did not cease to send him one letter after another. Among them were some Dutch art lovers who showed him (since Fame had already spread his reputation) that he would do as well with the prices of his work as in Rome. Whereupon he decided to depart from there, so that in 1639 he landed in Amsterdam. He went from there to live with his brother, who was a schoolmaster in Haarlem, where he painted many artworks which were later sold for a high price and more than he would have gotten for them in Rome, so that his work was bought up in Italy and sent to Holland

Page 363

to make a profit. I have seen many works by him which, although brown and sad, were very naturally rendered, like others that pleased me wonderfully well.

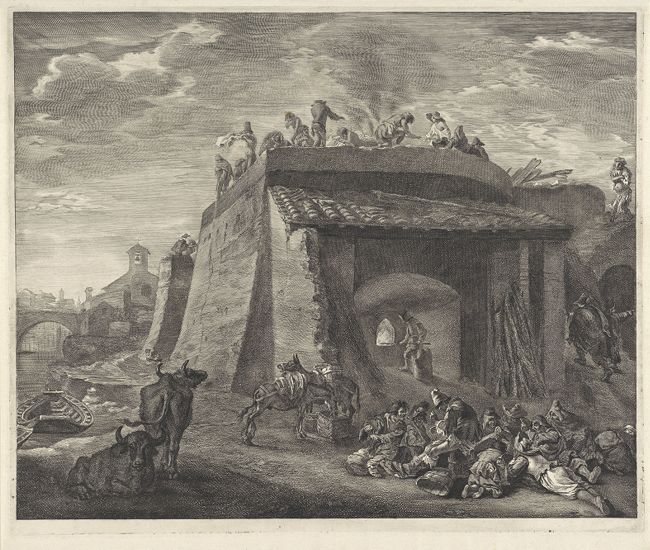

He often painted brigandages and Italian road houses. And everything that was depicted in them, both horses and people, was wonderfully inventively thought out and artfully painted. Several of his important pieces have come out in print, including a brigandage in a cave [1-2] and the so-called limekiln [3].

Having reached his sixtieth year, he was plagued by a congested chest which extinguished his courage. The melancholy to which he succumbed worsened his ailment so that, averse to living any longer, he drowned himself in a well. Samuel van Hoogstraten seems to confirm this clearly, since he writes on page 311 of his book: that Francesco Fiammingo [= François Du Quesnoy], dumbfounded by Bernini and saddened, used a noose to move on to the house of the shades, where Bamboccio, as they said, later went to search for him.

Thus the comedy of a man’s life is turned into a tragedy.

It happened that when Bamboccio was in Rome and backed up by four more Dutchmen, he met a certain papist (who had punished and threatened them over the eating of meat during Lent) and threw him in the water. Andries Both was also present and involved. And it has been observed and investigated that all five of them found their end in water.

I do not know the precise time of his birth, but the little that I know about him

1

Pieter van Laer

Attack of robbers in a cave, c. 1639-1642

Sint-Petersburg, Hermitage, inv./cat.nr. 6931

2

Cornelis Visscher (III) after Pieter van Laer

Attack of robbers in a cave, c. 1638-1658

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-62.116

3

Cornelis Visscher (III) after Pieter van Laer

The large lime kiln, 16361638-1658

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-62.117

Page 364

has me decide that he was born early in the sixteenth [sic] century, because he lived to his sixtieth year and, as Samuel van Hoogstraten wrote in his book on painting, he was already dead in 1675, as appears from what has just been adduced. He was therefore born around 1613. His portrait is in Plate R at the top, recognizable by his turned-up moustache.

This Bamboccio also had a brother [= Roeland van Laer] younger than he who also practiced the art of painting and was with him in Italy. But when he intended to ride his donkey over a bridge made of beams and wattle to cross over a cascade from one rocky hill to another, it collapsed, so that he drowned along with his donkey.

Gelderland, though not nearly as fruitful in the nurture of artist of the brush as other Dutch provinces, has still over time produced art practitioners who by their handsome products deserve that their memory be kept alive by being once more brought back on stage next to others. Among these was

NICOLAES van HELT STOCKADE, born in Nijmegen in 1613. Few of his best works are to be seen here in these parts, seeing that he spent his best time in Rome and Venice. Thus we must deduce the praise that his art deserves from rumour carried here from France (where he made various large work for the King [= Louis XIII] with Joachim von Sandrart) and Sweden.

His figures were firmly drawn, softly plump

Page 365

and pleasingly painted, which is why they also pleased the eye of Queen Christina and the fine court of France.

He was still alive in 1662.

It is witnessed about him that he always showed subjects with his brush which had often been depicted by others in a different guise and also deliberately mirrored a different moment in time* in the subjects, as for instance in his Andromeda,

--------

* Moment in time) In olden days painters did not heed a moment in time, but often depicted the histories in their sequence, as for example, various Adams and Eves in the same scene: here where they are formed by the Creator, there where they hide in embarrassment. In addition we see where they are driven from the Garden of Eden and, finally in the distance, where Adam works the fields. I have also seen Cain when he sacrifices, then when he kills his brother Abel, and then when he flees, all in the same piece. I have even seen a piece by Abraham Bloemaert, one of our oldest and most famous masters, in which Juno was depicted gathering the eyes of the severed head of Argus to decorate the tails of her peacocks. And in the distance the sleeping Argus and Mercury with raised sword, ready to deal the blow, were depicted. But the later art practitioners have heeded the moment in time, this being that a history only shows what transpired in a moment, and therefore found opportunity to capture the manifold changes and incidents in other scenes.

Accordingly Mister Gerard van Loon says on p. 99 of his Inleiding tot de hedendaagsche penningkunde, such medals are to be dismissed on which the depicted matters are of such a nature that they could not have occurred at any one moment in time. For example, one may never depict on one and the same coin, the beginning of a battle, the surrender of the city, and the sack of the enemy’s possessions, while this can’t all happen in any one moment in time.

Page 366

daughter of Cepheus, king of the Moors,† and Cassiopeia, for what pride she had to undergo that sad fate.

Most have shown Andromeda with teary eyes raised to heaven, or when with pallor on the lips looks back at the sea monster and therefore laments:

Oh Rock! oh Rock! hear my sighs and unlock

These chains, or spit out these iron clamps.

I see the monster from afar, tearing through the spacious brine.

Help! Help! From whom is aid now to be expected.

But our Helt [= hero] depicted her freed from the rock, looking down blushing with shame, which Ludolf Smids examines, introducing Perseus speaking thus:

Andromeda! Permit me to free your soft hand

From this hard iron: the monster is defeated,

And floats here with carved up intestines.

Reach out. You will wear pearls instead of iron.

Do not be ashamed before Perseus. He lowers his eyes,

Not to offend them with the glow of nude body members.

Nor weep, oh beautiful one, weep no longer.

Compel the sadness and shame to leave you.

--------

† Andromeda was Moorish. But to the best of my knowledge not one of the early or recent painters has heeded the truth of the history in that respect, but all have used Ovid, who says: truly a sea breeze stirred up her hair, and Perseus saw the lukewarm tears leaking down her cheeks. He will have thought that it was a marble statue, etc. This was possibly because they did not know or else took that freedom, seeing that a tanned skin is not as pleasing to the eye as a white skin.

Page 367

Joost van den Vondel also thought it worth his while to cut his pen to commemorate some of the gems of his Rymoeffeningen, namely the Cloelia with Mister Hoogenhuis. About which he says:

The Roman Cloelia escaped swimming with noble maidens

The taking of hostage and the eye of the guard and of death:

Which is why she pleased Porsena and all of the Council, so that

Demanded by the enemy, she received an equestrian statue.

And about the distribution of grain by Joseph in Egypt [4].

The guardian of the state brings treasure and succour to all of Egypt

Which now lives for seven years on the extended grain.

Through need, the free people become the king’s own slaves

One man’s caution can betray thousands.

Thus also Jan Vos on the same piece in the treasury.

Hunger forces the people to Joseph’s barn for grain.

His precaution is a fortress for country and subject:

On the Y, in wealth, they look after support in other days

The keepers of treasure are a blessing for the burghers.

One sees his portrait at the top of Plate R, to the left of Bamboccio.

It is taken for one of the lucid propositions of natural science that individual nature and inclination as well as the similarity of features and other characteristics are passed on in or from

4

Nicolaes van Helt Stockade

Joseph sells grain to the Egyptians, dated 1656

Amsterdam, Koninklijk Paleis (Paleis op de Dam)

Page 368

father to child in procreation, which daily examples will confirm.

Adam Willaerts, whom we considered on page 60, was a commendable painter and his son ABRAHAM WILLAERTS was inclined this way from his youth on. He was born in Utrecht in 1613 and learned the first basics of art from his father and then for a year from Jan van Bijlert. After that he joined Simon Vouet in Paris, where he made such good use of his time and progressed so far through industry and diligence that, having returned to Utrecht, he was summoned to Brussels by Count Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen to draw some things and to paint. But it is not clear what went wrong or for what reason he sailed with the fleet to Africa and, having disembarked, went to the city of Sao Paulo in Angola. But they say that upon his return he was more esteemed by the count than before. He later practiced art for a long time in Amersfoort and also as assistant to Jacob van Campen, who was a renowned architect and art expert. In addition he was inclined to help along youths in whom he saw a good spirit and to share generously of his intellect with them. In that connection we will also praise him in the biography of Matthias Withoos. Willaerts was still alive in 1660 and lived in Utrecht.

In that same year, 1613, was also born in Brussels JACQUES D’ARTHOIS. He was famous for his naturally loose and soft handling with respect to skies and able inventively to paint recession and trees with trunks overgrown with moss or

Page 369

covered in ivy and to decorate his landscape with well-formed figures.

Here one saw Celadon with his woolly sheep.

There one saw Coridon sleeping with Amarillis.*

Here the land was ploughed near a bucolic village.

There one mows the grain, or other summer fruit.

Here they hurry to the hunt to the growling of the horn

There one sees pursuit of the hare’s tracks in wind and rain.

Here sits a shepherd lad, rested in the grass and plays

A rural tune on his flute, while his buddy sings.

Here stands a farmer girl, listening to voice and flute.

Forgets perchance her cattle (the day already darkening)

To drive them to the stable before the fall of night.

Information which in doubtful matters must be taken for guesses might often have confused me (if I had not used careful consideration) as, for example, with the famous painter Bartholomeus Breenbergh. In his case some would wish to assure me that he was born in Utrecht and was the master of Cornelis Poelenburch.

--------

* Amaryllis was not so much used as a proper name than as an appellation between lovers. That is why Ludolf Smids, in his commentary on the love poetry of Ovid, says: This presumably refers to the Amarilletje of the chaste Mantuan; being a lover of chestnuts, as Virgil himself relates in the second Bucolics. Etc.