4. Poets and Poetry in De groote schouburgh

1

Cornelis Visscher (III)

Portrait of Joost van den Vondel (1587-1679), 1657 (dated)

Vienna, Graphische Sammlung Albertina, inv./cat.nr. 17601

2

Ludolf Bakhuizen

Portrait of Johannes Antonides van der Goes (1647-1684), dated 1680

Amsterdam, Universiteit van Amsterdam, inv./cat.nr. 000.047

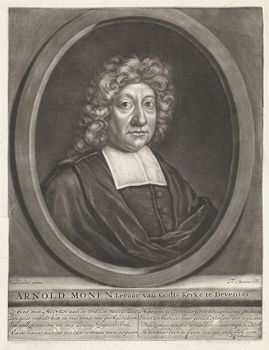

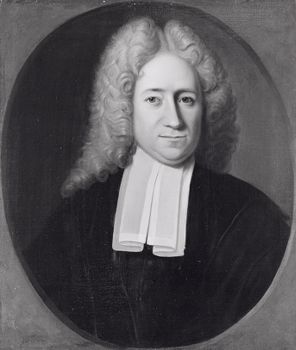

Poems can also present problems. De groote schouburgh features a great many of them, written by numerous poets, most of them now forgotten. Both Joost van den Vondel (1587-1679) and Johannes Antonides van der Goes (1647-1684) are still well kown [1-2]. Readers should also know that when Houbraken refers to an unidentified ‘choice poet’ or ‘the great Agrippian’, he intends Van den Vondel, whereas the ‘Amstelstroom writer’ or ‘Ystroom writer’ is Van der Goes. In one instance, Houbraken quotes an eloquent fragment from De Ystroom without giving the poet credit.1 In the case of the two most famous poets of antiquity, Houbraken refers to Virgil as Maro (for Publius Vergilius Maro) and to Ovid as Naso (for Publius Ovidius Naso), or to. A less well-known example is Petrus Scriverius (1576-1660) [3], whom Houbraken calls Pieter Schryver by his more humble Dutch moniker. In addition there are Caspar van Baerle or Barleus (1584-1648) [4], Joan Leonardsz Blasius (1639-1707), Nicolaas van Brakel (dates unknown), Joan van Broekhuizen (1649-1707) [5], Harmanus van den Burg (1682-1752) [6], Willem Jacobsz. van Heemskerk (1613-1692) [7], Willem van der Hoeven (1653-1727), David van Hoogstraten (1658-1724, Ludolf Smids (1649-1720) [8] and Jan Vos (c. 1610-1667) [9].2 There is also the poetry as translated by the likes of Arnold Hoogvliet (1687-1763) [10], Arnold Moonen (1644-1711) [11], Andries Pels (1631-1681) [12] and Joannes Vollenhove (1631-1708) [13]. The rhyme and quality of their poems have presumably been lost in translation. It is clear, however, that poetry was much more important for Houbraken’s readers than it is for us. That it was an important selling feature of De groote Schouburgh is established by an anonymous and appreciative review of Part I, published in April of 1718.3

3

Pieter Schenk (I)

Portrait of Ludolf Smids (1649-1720)

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

4

Willem Jacobsz. Delff after David Bailly

Portrait of Caspar van Baerle (Caspar Barlaeus) (1584-1648), 1625 of later

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

5

Ludolf Bakhuizen

Portrait of Joan van Broekhuizen (1649-1707), c. 1700

Private collection

6

Pieter Tanjé after Jan Maurits Quinkhard

Portrait of the poet and writer Hermanus van den Burg (1682-1752), 1752-1754

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-65.034

7

Jan van Mieris

Portrait of Willem van Heemskerck (1613-1692), 1687 of eerder

Leiden, Museum De Lakenhal

8

Bartholomeus van der Helst

Portrait of Peter Scriverius (1576-1660), 1651 (dated)

Leiden, Museum De Lakenhal, inv./cat.nr. 1445

9

Jan Lievens

Portrait of Jan Vos (c. 1610-1667), c. 1660

Frankfurt am Main, Graphische Sammlung im Städelschen Kunstinstitut, inv./cat.nr. 836

10

Jacob Houbraken after Dionys van Nijmegen published by Jan Daniel Beman

Portrait of Arnold Hoogvliet (1687-1763), 1745 (dated)

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

11

Frederik Boonen after C. Kelder

Portrait of the preacher and poet Arnold Moonen (1644-1711), c. 1700-1710

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1881-A-4825

12

Arnoud van Halen

Portrait of the writer and poet Andries Pels (1631-1681), 1700-1732

Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, inv./cat.nr. SB 5781

13

Hendrick ten Oever

Portrait of Joannes Vollenhove (1631-1708), 1687 (dated)

Zwolle, Stedelijk Museum Zwolle, inv./cat.nr. 382

In a class of its own are six lines in praise of Jan Davidsz. de Heem (1606-1684) and his unrivalled ability to make gold and silver look like the real thing.4 What is highly unusual is that Houbraken is silent about his source, which was a poem by the now obscure Arnold Nachtegael Klemens (1694-after 1729) found in his Mengeldichten (Mixed Poetry), which first came out in 1726.5 Obviously this was well after Houbraken’s death, but when we consult Nachtegael Klemens we find 1716 written in Roman numerals below the poem, which was presumably the original publication date. Even then we still don’t know where Houbraken found the poem. We must consider, however, that he did not identify the author of a poem on at least ten other occasions. Most important is a long poem which closes the short biography of Peter Snayers (1592-1667).6 Another two items concern still lifes by Pieter van der Willigen (1634-1694) and a third accompanies a pastoral landscape by Jacques d’Arthois (1613-1686).7 Two more short examples crop up in the biographies of Andries Both (1611/2-1642) and his brother Jan (1615/22-1652),8 Joannes Fijt (1611-1661), Peter Thijs (1624-1677), and Nicolaes Maes (1634-1693) garner one anonymous poem each.9 Finally, a set of three items (one of them only two lines long) grace the Life of Jan de Baen (1633-1702).10

A splendid example occurs when Houbraken sums up those who have written poetry in praise of the scissor art of Johanna Koerten (1650-1715): ‘In addition to those whose names have already been mentioned, there were Kaspar and Jan Brant, the Feitamaas, J.B. Wellekens, A. Bogaert, C. Bruin, Professor A. Reelant, and others too many to name’.11 To locate these worthies online one needs to look under Caspar Brandt (1653-1696) [14], Joannes Brandt (1660-1708), Jan Baptist Wellekens (1658-1726), Abraham Bogaert (1683-1727) [15], Claas Bruin (1671-1732) [16] and Adriaan Reeland (1676-1718) [17]. The Feitamas, who were also truly important art collectors, were Sybrand I (1620-1701) and his sons Isaac (1666-1709) and Eduard (1662-1737).12 In his short Life of Joris Cornelisz. van der Hagen (1676-1735), whom he calls J. van Hagen, Houbraken identifies the accommodating collector of this artist’s drawings as Eduard.13 As for Gezine Brit (c. 1699-1749), Houbraken devotes nine pages to an integral quotation of her poem Koridon, which sings the praise of Koerten.14

Houbraken can also be remarkably uneven. For instance, with three elegies by Willem van der Hoeven in connection with Melchior d’Hondecoeter (1635/6-1695), Gerard de Lairesse (1641-1711) and Jacob de Heusch (1656-1701),15 only the one dedicated to De Lairesse is documented.16 In general Houbraken’s presentation of his heterogeneous material is far from immaculate. Names, for instance, may be misspelled, so that Arnold Moonen (1644-1711) becomes A. Monen.17 Nor does an accurate title guarantee a correct author. Thus the Mengelpoëzy by H. van den Borg18 turns out to be by Hermanus van den Burg (1682-1752). Finally all Houbraken’s transcriptions of Vondel and other poets should be checked. For instance, in a quotation from Antonides van der Goes’ ‘Zege der schilderkunst’ (‘schilderkonst’ according to Houbraken), we find ‘smoort’ (smothers) changed into ‘vermoeit’ (fatigues).19 The curiosity in this instance is that Van der Goes makes sense and Houbraken does not. In the case of prolific poets, notably Vondel but also Jan Vos, unidentified poems can truly be needles in haystacks of publications. In addition references by Vondel and others to baffling names need to be traced to identify someone such as ‘Noyen’20 as the forgotten poet Ernst Noyen (fl. 1628-1659). Such detailed research will have to await a Houbraken corpus or specialized publications.

Houbraken was himself an accomplished poet, as we learn at once from his lengthy introductory poem to Part I of De groote schouburgh. In addition several other poems are certainly by his hand. There is a short poem that compares Johannes Torrentius (1588-1644) to the Greek arsonist Herostratos,21 for which he explicitly takes credit. A longer poem of his describes the subject matter of the paintings of Adriaen Brouwer (1603/5-1638).22 Houbraken also thrice quotes poetry from his still unpublished emblem book.23 A substantial poem of his closes the brief Life of Anthony Vreem (1656-1681), whereas an eight-line item is enclosed in the Life of Adriaen van der Werff (1659-1722).24 Finally a poem filling most of two pages, which is dedicated to Flora and the field nymphs as inviting pastoral subject matter, would also appear to be by the biographer.25 It therefore seems likely that he wrote some of the anonymous items as well.

As a closing consideration Houbraken may quote a poem which contradicts his text. That, for instance, is the case with a poem underneath a portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678) which was engraved by Jan van Munnickhuysen (c. 1655-after 1701) [18]. Where Houbraken presents her conversion to ‘the Labadist zealotry’ as an unmitigated disaster, the anonymous poet presents it as the glorious culmination of her life.26

Here you see the noble maid, called matchless,

Before she chose a better lot over worldly praise.

She was as if composed of wisdom, spirit and virtue:

Art, languages, scholarship, learning, honour,

She gladly lays before Christ’s feet.

The question is whether Houbraken intended to be ironic or whether, ever unselective, he simply included the poem because he had come across it.

14

Jacob Houbraken after Michiel van Musscher

Portrait of Caspar Brandt (1653-1696)

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

15

Nicolaas Verkolje

Portrait of Abraham Bogaert (1663-1727), dated 1720

Haarlem, Teylers Museum

16

Jan Maurits Quinkhard after Norbert van Bloemen

Portrait of Claas Bruin (1671-1732), c. 1733

Haarlem, Teylers Museum, inv./cat.nr. pp207

17

attributed to Johan George Colasius

Portrait of Adriaan Reeland (1676-1718), before 1711

Utrecht, Universiteit Utrecht

18

Jan van Munnickhuysen possibly after David van der Plas published by Jacob van de Velde (uitgever)

Portrait of Anna Maria van Schurman (1607-1678)

The Hague, RKD – Nederlands Instituut voor Kunstgeschiedenis (Collectie Iconografisch Bureau)

Notes

1 Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, p. 329, as spotted by Carasso 1996, p. 335.

2 For even more poets: Swillens 1944, p. XXXV.

3 This review was first published by Bart Cornelis: Cornelis 1998, p. 152.

4 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, p. 211.

5 The poem appears on page 55 of his Mengeldichten of that year. On the confusion of Arnout Naghtegael (1658-1737) and his son Arnold Nachtegaal (1694-after 1729): Fuchs 2016 and Fuchs 2017.

6 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, pp. 151-152.

7 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, pp. 288 and 369.

8 Houbraken Translated, vol. 2, p. 116.

9 Houbraken 1719, pp. 143 and 277.

10 Houbraken Translated, vol. 2, pp. 307-308.

11 Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, p. 296.

12 The collective holdings of the Feitama dynasty ended up being described by Sybrand’s grandson and Isaac’s son Sybrand II (1694-1758), as published by Ben Broos in 1984, 1985 and 1987 (as listed in the bibliography below). In 1735 Sybrand II wrote two poems commemorating Koerten and added them to the family album with all the Latin and Dutch poems praising her cutting art.

13 Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, p. 203. Eduard Feitama first shows up on Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, p. 57, in connection with a proof for an engraving by Geertruydt Roghman (1625-1651) based on a portrait of Roelant Savery by Paulus Moreelse (RKDimages 165984). Eduard Feitama does not crop up in Ben Broos’ three articles about the Feitamas as collectors.

14 Again Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, pp. 297-305.

15 Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, pp. 70-71, 130-131 and 366-367.

16 The publication in question, dated 1711, is repeated in the bibliography below. For the two others we suggest the collection of Van den Hoeven’s elegies of 1703, also listed in the bibliography.

17 Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, p. 295.

18 Again Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, p. 370, note †.

19 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, p. 41. We have followed Van der Goes instead of Houbraken.

20 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, p. 148.

21 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, p. 139. This poem was praised in the anonymous review of April 1718.

22 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, p. 328.

23 Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, p. 122.

24 Houbraken Translated, vol. 3, pp. 384-385 and 392.

25 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, p. 328.

26 Houbraken Translated, vol. 1, p. 316.