Volume 3, page 260-269

Page 260

perfect beauty with what nature sowed him. But he was all too free in his depictions. People accuse him no less of the liveliness of his spirit and the abuse of his precious gifts by making subjects which shame and honour are not permitted to observe, or else they must be seen with contempt and detest the maker along with the product.

MARCANTONIO RAIMONDI of Bologna has rendered 20 prints in copper after drawings by Giulio Romano, and Pietro Aretino made captions in verse, including some just as lascivious and rude as the depictions. But if Giulio Romano had not left Rome in time, the anger of the Pope could have paid him for his troubles. Because as soon as Clement VIII got wind of it he had Marcantonio thrown in prison, where he would have lost his life if he had not found a means by which he escaped handily and had not the intercession of Cardinal de Medici and Baccio Bandinelli saved him from further persecution.

It is not the purpose of this speech to set limits to art practitioners in their preferences but purely to recommend to new arrivals, should they develop inclination to matters and acts which consist of loose playfulness, that they do not discover impure or erotic tricks but keep things under control. At least that for which an honourable eye has dislike should clearly

Page 261

not be depicted as Raimond Lafage, Budart [= Pierre Bodart?], Gerard de Lairesse and others have done. Arnobius, speaking about the sacred object of the Telesterion which is carried around the Eleusis (instituted on account of the wandering of Ceres searching for her abducted daughter), says that it remained covered with such close supervision that few got to see it. Read also about the same disguised secrets in Horace, 3. B. 2.

As an example to show that such depictions or displays that offend an honourable face can be handled circumspectly, without the depictions losing their meaning or becoming unrecognizable, serves our print illustration of the garden god Priapus in Plate 17 of the 2nd volume of our Emblems [1], where he is depicted in such a guise as we encountered him in Roman antiquities, with long reed or reed grass on his head, to scare off or drive away the birds by his own steady movements, so that these do not damage the fruit. The folds of his cloak (of which the train is weighted down by the heaviness of the fruit), announce clearly enough the stiff shaft that hides below, by which the power of procreation is indicated, as is horticulture by the garden knife. There are thousands of subjects on which reflection of the human intellect and the art brush can practice without offending the honourable eye or stir a youthful heart to inappropriate affection.

All of nature, and her countless manifestations, which she displays by alternation (as proof of her wonderful power) are, down to

1

Arnold Houbraken

The fertility god Priapus, c. 1675-1700

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1885-A-8997

Page 262

the very least, objects that the brush can work on until worn down without imitating this perfection with equal form and colour.

What changes does she not constantly show in her seasons in flowers, the adornment of gardens! To which so many of our painters and paintresses, of old as now, have applied their efforts, seduced to imitate their beauty, tenderness, and splendid colours.

Can the birds, which flutter with their swift wings through thin air, making the forest resound with their sweet song and hopping from branch to branch pursuing each other, not charm your urge to paint? Or cannot the defenceless animals of the field, little sheep, goat and lambs, as they skilfully trim the dewy morning grass or reflect themselves in a pool while drinking, not gratify your desire to emulate?

Can the ocean, plied by floating palaces; can the changing aspects given to it by the changeable sea and the howling north wind, or the misty inland waters, where pleasure yachts, decorated with sculpture and gilding and many other small ships show themselves between the green dikes that serve as protection for the rural districts, not tempt you to emulation? Or can’t the wild boar and deer hunt (the delight of the greatest rulers on earth), or the elegance of its accoutrements, or the courtly retinue, set your painter's passion in motion?

Are such subjects too trivial to invest your energy in them? Never mind, there is material enough. Imagine a country lad with his lass next door under the

Page 266 [= 263]

foliage of a thickly tressed linden tree or a rustling creek with woolly cattle, or have him lilting a love tune for his sweetheart on his shepherd's flute. Thus the brush moves effortlessly from that subject to the accoutrements of small oxen, sheep, goat, herbs in the foreground, trees, and deeply receding green meadows.

Is this still too common for an ambitious intellect? Open the Roman history books, or the Bible. They will provide you with ample material for your selection on which to practise your intellect and brush.

Is this not able to charm you, because the majority of these subjects yield tragic material or serious depictions? Is your spirit not able to accommodate itself to the exactness of keeping to the letter of a historical description?

We don't wish to frustrate anyone in his inclinations: but as for me, I have always preferred serious history to farce, because I found more opportunity there for the depiction of all sorts of powerful emotions. However, I have always had an aversion to depicting human slaughter at that point in time that the bloodletting actually occurs, but not when the preparations are done and one sees the fatal knife on the throat or the axe raised, as I depicted it for Mister van Heemskerk [= Johan Hendrik van Heemskerk] in The Hague, with Orestes and Pylades, their intention betrayed by the Oracle, seized by Thoas, and brought as temple despoilers before the altar to be slaughtered before the eyes of the people, but saved by their mutually faithful love for each other. For

Page 264

The true Orestes, needing his Pylades,

Called out in a loud voice: The prince has misled you,

I am Orestes, I. But the other controverted him.

What would the King do in this uncertainty?

But I have always avoided showing bloodshed, with which one at once feels a chilling of the blood when one sees it.

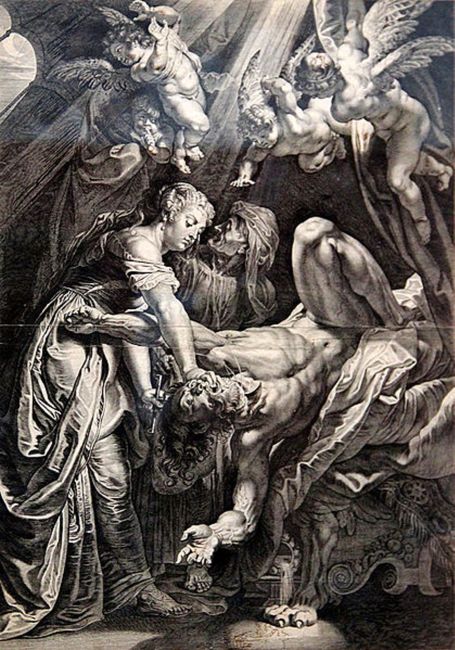

I have seen the beheading of Holofernes by Judith by Rubens [2] and the beheaded trunk of Goliath by David Spanjolet [= Jusepe de Ribera], as well as the marvellously artfully painted Proteus by the latter. But as for me, I would sooner, given the choice, see a stark-naked Eve without fig leaf, a well painted figure of Venus standing nude, or a softly sleeping nymph, spied on by a sweet-toothed cloven hoof, to catch her if she were not guarded, as is shown in the print opposite. People should cover such terrible bloody displays with curtains, which is why such plays are currently rejected from the theatre.

Thus Medea may not kill her offspring before the people,

Nor Atreus, to invite to the flesh of children,

Their own father, who cuts the throats, fries

And cooks them before the eye.

But you may well have more appetite for happy features than wrinkled foreheads. Certainly there are enough gratifying and joyful subjects at hand on which to practice the brush. It may be that you depict field nymphs in a row going to Ceres’ statue, or where

2

Cornelis Galle (I) after design of Peter Paul Rubens

Judith beheading Holofernes (Judith 10-13), after 1609

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France

Page 265

they dance around hand in hand with satyrs, or a feast of Bacchus. The art practitioner nods to me. It appears that I have finally guessed it.

There are people (says Baltasar Gracián) who are gifted with all sorts of unusual politeness that endears them to everyone and has them well-received. The first, most pleasant part of this praiseworthy gift consists of the general knowledge of everything that happens in the world, an observation of all the praiseworthy acts of rulers, the unusual instances of the miracles of nature and the excesses of fortune, and apply them at the right time. By means of this capability and moral dissection he can judge matters healthily and take the measure in feet of truth. Above all he makes an accurate collection of all good sayings and of all amusement, be they distinguished as entertaining, and has sayings of the wise in ready supply to be pleasing to the world.

These gifts possessed the artful chassinet [= window pane cover] and landscape painter JAN van NICKELEN, born in Haarlem, who, as appeared from the result, was able to employ them wonderfully well.

His father [= Isaak van Nickelen], who was a handsome painter of churches in the manner of Hendrick van Vliet, and who later taught him the architectural and perspectival aspects of the brush, first took him to French and Latin schools, to be instructed in languages, in which he made gratifying progress thanks to his intellect and good memory. Then,

Page 266

being a curious reader, he became accomplished in histories, travel descriptions, natural sciences, and the Bible and foundations of religion, being daily in the religious meeting places and with such people as amongst the Mennonites are called Socinian Disputants, by which his intellect became ever keener.

Tireless in the investigation of all sorts of sciences, he discovered this or that. He also invented an incomparably hard lacquer with which he lacquered cabinets, fancy side tables etc. just as well as the Indians. Later on he discovered something exceptional with respect to loom works or weaving mills, seeking partnership with people who had lots of money, and patent protection from the States. But nothing came of it. He therefore turned to the painting of landscapes, flowers and other ornaments on thin silk, serving as covers for glass panes, as well as lacquer work etc. Whenever he had drunk a glass more than usual, he was full of all sorts of pranks and jokes and was able to play the part of the Quaker marvellously and to compose an occasional verse on the spot (as the saying goes).

Here in Amsterdam, he was able to enter the favour of the painter Herman van der Mijn so well with his velvet tongue that he, having been summoned by the Elector Palatine, took him along at his own expense, where he at once made friends with Mister Jan Frans van Douven, court painter and keeper of art of the ruler, of which he was able to make such good use that he no longer had need of him. The first time that he spoke to Douven

Page 367 [= 267]

he was able to present his own interests so well that he at once had him make some ‘chassinetten’ without the knowledge of the ruler and place the same on a spot where the ruler had to pass, to thus surprise him with these adornments. They pleased the Elector, who at once ordered him to render some of his country residences, with their green lanes, gardens, fountains, etc. after life and to paint them, to which to their greater enhancement, he added some hunts, or a shepherd or shepherdess

next to the rustling of a well,

And silver rivulets, where against the piercing sun

Extends cool foliage to the richly forested valley.

It came to pass that the ruler showed him a piece by the painter Adriaen van der Werff on which to pass judgment, and also a portrait by Douven. He praised the first according to its worth, but with the lament that Van der Werff was disadvantaged by the proximity of Douven's portrait, which was so boldly and naturally painted. Thus he killed two birds with one stone, by which the latter suffered no disservice. He certainly was at least as prominent at the court thanks to his polished tongue as Van der Mijn by his commendable art.

After the death of this elector he came to the court of Hessen-Cassel.

We saw the preceding century close with the igniting of the great light of art Anthony van Dyck. This half century of the sixteen hundreds also does not come to an end without the art goddess igniting an illuminating torch of art to shine on and illuminate the second half of the 17th century

Page 268

in the person of AUGUSTINUS TERWESTEN I, born in The Hague on the 4th of May 1649. He spent his spring years first with drawing after prints and plaster, later with modelling in wax, which led him to metal chasing, of which he worked various samples both in gold and silver with great fame. Not satisfied with this praise, while his spirit aimed at greater undertakings, he revealed his intention (having now become around twenty years old) to his parents, adding that he had firmly decided either to marry or to leave them the choice to decide what they most wanted him to do. His parents, who chose the better of the two, allowed him to study the art of painting. They also placed him with the famous painter Nicolaes Willingh. But he only enjoyed two years with this court painter appointed by Friedrich Wilhelm Elector of Brandenburg, after which he went on to learn the mixing of paints and brush handling with Willem Doudijns for two years, in which time he progressed so far in art that he decided, to reach greater perfection in art, to take a journey through Germany to Italy, where he remained for three consecutive years, diligently practicing after the best models for which one goes to Rome, such as the famous marble antiques and the brushwork of Raphael, after which he made detailed drawings to make use of them later on.

After he had let himself be detained in Venice for some month, he undertook the return journey to his native city through France and via England,

Page 269

having spent a total of six years on that journey, after which he arrived home in the year 1678.

He made various great art works, both rooms and ceiling pieces during his journey and later on, in addition to other art works, for which one could compile a whole list (seeing he was wonderfully deft with the brush).

I further remember that when he painted the room of Mister Barthout van Slingelandt, later burgomaster and chief bailiff in Dordrecht, in the round with histories from Ovid. I went to visit him in the company of the painter Arent de Gelder and the commendable sculptor Hendrik Noteman, intending to tempt him into taking a walk. But he declined politely under the pretence that he still had something to do which necessarily needed doing, with the request that we would be so good as to return after an hour or two. We did this and then found to our amazement a chimneypiece with three or four figures, entirely rendered in colours, which had only been indicated with chalk when we first came by.

He was one of the most important strivers who helped reconstruct and support the Hague Academy, now fallen into decline, in the years 1682 and 1683, a matter of great use to art practitioners and the less experienced, or new arrivals, which is why he later also erected the Advanced School on ‘s Vorsten Beurs, which