Volume 3, page 230-239

Page 230

he tried to imitate the famous Titian.

Amongst a multitude of portraits that he painted is reckoned that of Cornelis Tromp, vice admiral of Holland [1], whose memory is preserved by the following verse by Ludolf Smids.

How all the top brushes,

In Athens competed for money or favour,

To portray ruler Theseus in their scenes,

With power and art:

Parrhasius began to paint

That proud and distinguished face;

But was not able to obtain the victory.

The lows are too tender and light,

And the highs much too softly raised,

And effeminately blended.

Eufranor’s Theseus shows power

In all the lines of his features;

The divine portrait has flesh and blood,

Swollen muscles, strong sinew,

And eyes which with their glance

Penetrate the heart of his Athenians,

Whip it with fear and fright,

And force it thus to sing his praise.

Parrhasius see, this one wins,

His is a hero and yours a child.

Thus your Tromp will also triumph,

Renowned painter Van der Plas,

And burn, which you dare brave,

And taunt with his glance to ashes.

1

David van der Plas

Portrait of Cornelis Maartensz Tromp (1629-1691), second half 1670s

Rotterdam, Museum Rotterdam, inv./cat.nr. 10546

Page 231

Does not this portrait appear to wage war?

It flashes from that great face,

On the one yonder which, as part of the attempt,

A courtier, and not a soldier.

Oh Spirit! Oh hand! Oh bold paints!

Never let your commendable master die.

He spent several consecutive years with the book dealer Pieter Mortier with improving, altering, or checking of proofs for biblical scenes, by which he demonstrated that he well understood the coupling of light and dark, and the harmony and elegance that are required for illustrative work. But he did not live long after the completion of this work, having to accept death (the fate of all men) on the 18th of May 1704.

Who can take advantage of it? After his death people saw various satires rhymed by one of the plate setters knocking about.

DANIEL SEITER, bent-named the Morning Star or Cavalier Danielle, was born in Vienna, in Austria or, as others would have it, on the borders of Switzerland and raised in Vienna. Be that as it may, the praise of his elevated art still dwells on the tongues of those who have travelled to Italy.

I know not who his first teacher was, but he painted for a long time in Venice with the famous Johann Carl Loth and imitated many of his works with his brush so that, dispersed everywhere, they are often taken for and sold as genuine works. Even in Italy (where one sometimes sees 2 or 3 pieces with the same content) they dispute about which one is genuine.

Page 232

After he had been in Venice for a long time and had mastered the Venetian way of painting and colouring, he left for Rome to further perfect the art of drawing (for which those of Rome are famous). To which end he sought out the supervision of Carlo Maratta, after which he came to marry a book seller’s daughter and a little later entered the service of the Duke of Savoy [= Vittorio Amedeo di Savoia II], who had great respect for him and for his art and as proof knighted him. However, in between time he was in Rome at various times and made important art works.

He particularly demonstrated his divine art of painting and drawing in large pieces in the Chiesa Nuova di San Filippo Neri, also known as the New Church. In one of them Manna rains in the desert with all of Israel, men, woman and children, busy gathering [2]. In another one sees the Last Supper of Christ, with all the figures life size and so artful in arrangement and natural expression of the passions and other required matters that the work will adequately immortalize his glory.

To give the mind a little relaxation now and then and not always to have it strained with great works, he would occasionally make a portrait, which makes me think of a certain advantageous incident about which the painter Jakob Christof Le Blon told me. When he was going to finish painting the Duke of Savoy, his patron, he had forgotten his maulstick. The Duke, seeing him embarrassed, handed him his walking cane

2

Daniel Seiter

The manna falls to the earth (Exodus 16:17-18), 1697-1700

Rome, Chiesa Nuova - Santa Maria in Vallicella

Page 233

(studded with diamonds at the top), saying can I be of service to you with this? Our knight made use of it to lean on with his hand, and after he had completed the effigy, he wanted to give it back to the duke, but one of the courtiers, who favoured him, restrained him, saying quietly to him: the Ruler would take it as a kind of contempt; after all, he has asked can I serve you with this? and as a consequence will not ask it back; and if it is requisitioned from you afterwards by his guarda-Roba (keeper of the robe), get a signature for it. But he kept it and the mentioned Le Blon still saw him with it in the year 1687, when he was in Rome and must have reached fully 50 years. Because we have received no further news, we have placed the beginnings of his life in the year 1647. In the year 1699 the painter Gerardus Wigmana saw him in good health in Rome, and I have thus far heard nothing about his death.

GOTTFRIED and JOHANN ZACHARIAS KNELLER, born in Lübeck in Hollstein, where their father was assistant sexton of the church, now follow. The latter painted buildings and landscapes and also at times small portraits in oil paints, but his art did not mount to the heights of his brother. Both travelled through Italy, England and Holland. Gottfried, born in 1648, was from his youth on inclined to art. After he had practiced it for some time he headed for Holland and instruction, first, from Rembrandt and then from Ferdinand Bol.

I do not know how long he enjoyed the instruction of mentioned masters, but I do know that he

Page 234

left from there to Rome and the sublime art of Titian and Annibale Carracci. He was first a history painter working in life size, for which he took up a bold handling of the brush which he still keeps and that has brought him much fame but less advantage than he hoped for. He therefore left history painting and took up portraiture, at which he succeeded. And people have seen with the passage of time that Fortune did not behave as a stepmother to him, but that he has truly been a favourite of hers, and still is.

He travelled by way of Nuremberg to see portrait painters in his fatherland. But the first step in his elevation was Hamburg, where he got to know Mister Jacob de le Boë, whom he painted with his wife and children in one work, and who from then on functioned as his Maecenas and knew how to trumpet about the worth of his art so well that it brought him handfuls of work and made his purse fat. From his experience of these changes in art he took for a common saying: History painters make the dead come alive; and they themselves only live after they are dead. But I paint the living and help myself to their favour.

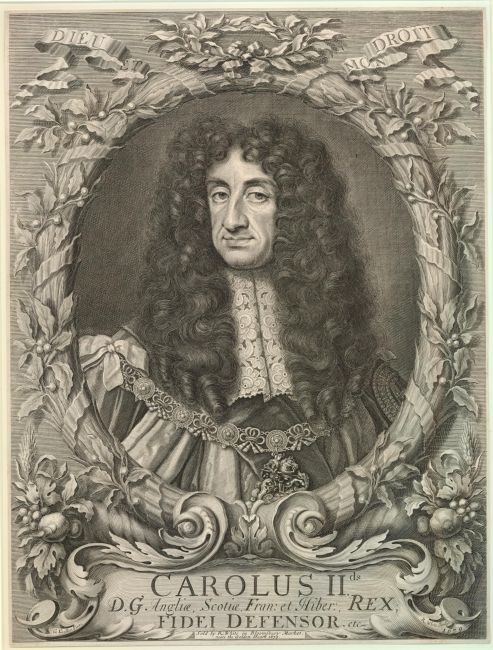

Shortly thereafter Peter Lely, who had flowered at the English court for many years, came to die. One man’s death (the proverb says) is another man’s sustenance. He at once went to England where he is able to see to it that he mixes with the great of the court and then enters into the favour of King Charles II, who knights him. Thus it was reported to me by French writers, but later

Page 235

information passed on to me in letters from London mention that he already arrived in England while Peter Lely was still alive. Where he was recommended to Sr. Jonathan Banks a Hamburg merchant living in London, whose portrait [3], as well as of his family, he painted. He was greatly pleased and introduced him to the Duke of Monmouth, whose portrait [4] he painted so much to the Duke's satisfaction that in one stroke he lifted him on to the fast track to fortune, on which he has since ambled along quite nicely. It did not take long until King Charles II would have his portrait painted for his brother, the Duke of York, by the King's painter, Sir Peter Lely. What happens? It is so arranged that Godfrey Kneller would paint at the same time. Lely placed the King and then himself. Kneller did likewise as best he could, and then both of them went to work. The King, rising, looked first at that of Lely and then at that of Kneller, and took great pleasure in the latter because he saw the features almost completed, whereas that by Lely was only in under paint. The Dukes of York and Monmouth, who were present, along with a lot of other people of state, did the same. But this was the nail in Lely's coffin. Nor did he live long after that, and Kneller became the king's painter in his stead [5-6].

After the passing of some time, King Charles II sent him to France to paint the king’s portrait after life. But before he returned from France with the portrait, King Charles had died. His brother James II, having ascended to the throne, had equal appreciation for his art and appointed him as

3

Gottfried Kneller

Portrait of John Banckes, dated 1676

London (England), Tate Gallery, inv./cat.nr. T05019

4

Gottfried Kneller

Portrait of James Scott, Duke of Monmouth, dated 1678

Boughton House (Northamptonshire), Bowhill House (estate), Montagu House (Bloomsbury), private collection Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry

5

Robert White after Gottfried Kneller

Portrait of King Charles II of England (1630-1685), dated 1679

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. P,5.6

6

(after?) Gottfried Kneller

Portrait of King Charles II of England (1630-1685), after 1676

Norfolk (county), private collection Earl of Townshend, inv./cat.nr. RN59

Page 236

first court painter. Later William, Prince of Orange came to the throne and had himself painted by him along with the Queen, and when the Peace of Rijswijk was to be closed, he sent him to Holland to paint the plenipotentiaries of the foreign courts after life for him and, having returned to England, honoured him with a knighthood.

Having come to the throne, Anne was at once thrice painted by him, each in an unusual way, as was her husband, Prince George of Denmark, with the young Duke of Gloucester. Shortly before her death mentioned Queen Anne made him nobleman of her cabinet. At this time, at the request of the Roman Emperor Joseph I, he also painted the portrait of Charles, his younger brother, who was about to leave England as King to Spain [7]. He liked the work so well that he declared him hereditary knight of the German Empire and gave him a golden chain with a medal on which his portrait was minted. He now has the wind in his sails with the present king, who as proof of his favour has made him a hereditary knight-baronet.

From that time until now, in which one writes, 1715, he has painted an innumerable number of portraits which have brought him both fame and great profit, so that good fortune has followed him on his heels like a shadow from the beginning.

And as far as his art is concerned, it deserves the highest praise because of the natural colour and well-arranged and loose clothing of the figures, the variety in the manner of

7

Gottfried Kneller

Portrait of Charles VI (1685-1740), Holy Roman Emperor from 1711, c. 1703-1704

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 404952

Page 237

standing and sitting, the great backgrounds and other graceful additions, and especially his lose touch and bold brush. In one word, he is a praiseworthy and fortunate painter.

But one and the other of his portraits differ in worth (as the saying goes) like apples and oranges. But the cause of this is that he sometimes had more competent painters in his service than at other times, and the one was better able to imitate his handling than another. Because it is acceptable in England that the masters do only the features and the hands, with the clothes and attributes done by others. But in Holland this would not pass for sound coinage, nor would dressing several portraits in one and the same costume.

He has much love for the art of commendable masters and often lauded the great militia piece by Bartholomeus van der Helst (which now hangs in the military council room in Amsterdam) with great praise [8]. In particular he also makes much of the matchless art of Anthony van Dyck. It is to be seen from his art works that he had observed that art with great concentration; because one sees the same nature shine through and not rarely that he derived something from that great artist. Lord Philip Warthon told me with his own mouth (when in the year 1713 I was at his estate in Winchendon) that Kneller had asked him to be able to paint two of the 32 portraits by Anthony van Dyck that he has hanging in one room, out of great respect that he had for that art of the brush. But this was refused him,

8

Bartholomeus van der Helst

Banquet at the Crossbowmen’s Guild in celebration of the Treaty of Münster, dated 1648

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. SK-C-2

Page 238

notwithstanding that he gave assurances that the same pieces would not be appropriated but would come back into the hands of the Lord or his heirs after his death; from which may be seen in passing what esteem the English in general have for the art of Van Dyck.

To bring our Lübeck phoenix to an end, I have to say that through his art and fortune he climbed so high to the top of honour that below his portrait, made after the one which graces the gallery of the Grand Duke of Florence [9] (which is a collection that consists of the portraits of the most esteemed Italian French, German and Dutch painters) one reads: Dominus Godfridus Kneller de Whiton, Sacri Romani Imperii & Mag. Brittanniae Baronettus: Nec non serenissimi Georgii, Mag. Brit. Reg. Interioris Camerae Aulicus, & Pictor Princeps. Ec.

JAN van KESSEL, born in Amsterdam in the year 1648, painted inventively, naturally and elaborately all kinds of domestic prospects, homesteads, farmer’s cottages, stone ovens and such subjects, which he first drew after life for his use. He is especially praised for depicting the winter season. I do not know if he claimed a family connection with Jan van Kessel, whom Cornelis de Bie praises so highly. He departed (after he had spent his entire lifetime in the practice of art) from here to eternity (the general fate of mankind) in the year 1698.

Now we give place to the commendable painter

9

Gottfried Kneller

Self portrait of Godfrey Kneller (1646-1723), 1706

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 1890, no. 1753

Page 239

GERARD HOET I, born in Zaltbommel on the 22nd of August of the year 1648, according to the dating then used in Gelderland. From his most tender years his inclination was to art, in which it was of use to him that his father was a glass painter. But even before he could draw, he knew how to draw the letters of the alphabet, even though he did not know their sounds. On his seventh year he made a history on glass from Ovid, which had been read to him by someone else because he could not yet read himself. His father concluded from this that he stood to become a painter and encouraged him to draw diligently. But he found no occasion to learn painting before his sixteenth year. But then Warnard van Rijsen came to live in Zaltbommel, with whom he worked for only one year because Van Rijsen moved and was not able to teach anyone in his home. Shortly thereafter Hoet’s father came to die, so that he felt obliged to help his brother with glass painting. Finally came the disastrous year of 1672, which stopped everything in its tracks, so that Hoet went to The Hague. About this time there came amongst the French a commander named Salis [= Rodolphe de Salis Zizers], a lover of art, who with his mother bought everything by Hoet that he could find and asked her to summon him from The Hague to paint for him. This later came about in the Land of Cleves, in Rees, where the commander lay in siege. Hoet found there some young painters from Utrecht, such as Jan van Bunnick, Justus van den Nypoort and Andries de With. The last mentioned, noticing the fecund mind of Hoet, tried to always have him around. This De With was therefore the reason why, preceded by him, Hoet was summoned