Volume 2, page 110-119

Page 110

possess much art, which would be stifled at its birth. He then dissuaded him from his intention with many arguments and let him walk away to the sloop that was tied to the side so as not to be seen by the muster masters, saying to the crew members Berg hem [= hide him]. This taken for a saying by those who first knew of this incident and later altered into a surname which he took on and kept to the end of his life.

Others hold that the name originated on the occasion of a fire, as cause that it was shouted (he still being only a child) Berg-hem. Which of these versions is true, I can’t say. The stories have only given me reason to point to the accidental origins of his name. Still, one could conclude from one thing or another that he lost his parents early on or that he was not closely supervised to secure his well-being. But the knight and painter Carel de Moor II has assured me that this nickname originated on the occasion that he had misbehaved badly, when his father, who was a rash man, followed him to the house of his teacher Jan van Goyen, threatening to bash in his head, whereupon van Goyen said to his other students: Berg hem, while holding back the father and taming his temper.

He was the son of PIETER CLAESZ. of Haarlem, who first painted fish and later small pieces which usually featured a table with all sorts of sugar pastry in

Page 111

a silver bowl or porcelain saucer etc. Other than his father, who was a common painter, our Berchem had various commendable masters as teachers of art, such as Jan van Goyen, Claes Moeyaert, Pieter de Grebber, Jan Wils and finally his cousin Jan Baptist Weenix, all of whom took pride in having lit such a bright light of art, just as he in turn was able to take pride in the multitude of students who grew into great masters in art through his instruction.

He was especially famous with respect to his teaching methods but also for being able to spur on youths to diligence, to which he often had sayings and verses at hand, such as this:

Never should you torture yourself, apprentices!

(Though learning involves effort,

And you often break your head over it

While another plays around),

Or gives up on the effort:

Think: I will again receive payment

For my effort and attain fame,

When the others go begging.

In addition he was amiable, polite and of irreproachable behaviour. Yes, he was a man of outstanding diligence, this not withstanding his sweet housewife [= Catharina Claesdr. de Groot], a daughter of the commendable landscape painter Jan Wils, who (when he sat quietly labouring at his work with great diligence and she heard no stirring from him) could sometimes bang against the ceiling from below with the handle of a dust mop

Page 112

to wake him, just in case he might have fallen asleep in front of his easel. Yes, she usually kept him so thoroughly stripped of money that when he sometimes saw handsome prints on sale, to which he was inclined, and his wife was not predisposed to advance him the money, he would borrow the required money from his disciples. And when he sold a piece of painting and had kept her nose out of it, he would then pinch off enough from the yield to pay the debts without her knowledge, thus avoiding all unpleasantry. I almost think that that good man should have read the booklet mentioned by Hendrik Doedijns in his Haegse Mercurius of 1 November 1698, which was being printed for the second time, to wit: The weathervane of women, very useful for the married man who looks to the eyes of his angel to see how her head is inclined.

He was so greatly inclined to artful drawings by Italian and other masters that he could not rest until he owned them. No less was his passion for prints, of which Jan Pietersz. Zomer has told me that he dared pay 60 guilders for a print by Raphael of Urbino. This was the massacre of the innocents with a pine tree [1]. As a consequence his bequeathed art on paper (which was sold in Amsterdam shortly after his death in the year 1683) fetched a goodly sum of money.

He was exceptionally diligent, as we have said, and also facile at painting and everything he made was usually sold even before he had completed it. Justus van Huysum I, who studied art with him in the year 1665 [= 1675], has told me that at that time he painted for a long while for a gentleman

1

Marcantonio Raimondi after Rafaël after Raphael

Massacre of the Innocents, c. 1511-1512

London (England), British Museum, inv./cat.nr. 1858,0417.1580

Page 113

who gave him 10 guilders a day, and that he usually sat in front of the easel from early in the morning until 4 o'clock in the afternoon, and did this with so much pleasure and amusement that he sometimes sang a tune while at it. Those who have seen him paint also witness that he painted as if it were child's play, which is also to be seen from the playful brush strokes throughout his work.

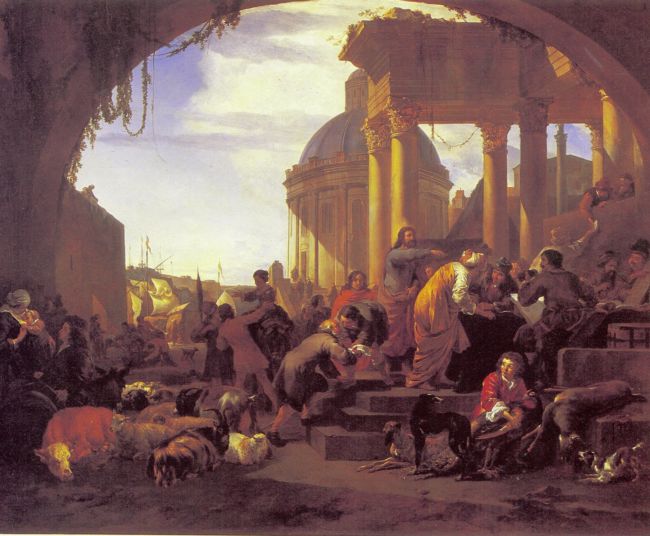

In addition it is astonishing that he applied himself to painting just about everything, but that each thing by itself is so good in its kind that once compared, it is difficult to say to which of them his brush was best suited. Only I have noticed that in a certain large piece (in which Matthew is called from the profession of the toll to that of an apostle) he helped himself to the brush of Jan Baptist Weenix for the dead game and birds [2]. This piece is presently in the hands of the heirs of the art-loving Mister Lambert van Hairen in Dordrecht, and teems with many figures, and is great in ordination and buildings as well as graceful because of its additions and recession.

But above all it is amazing that a man who painted so many pieces was able to think up such a multitude of arrangements and subjects (so that not one resembles another). The burgomaster van der Hulk in Dordrecht had him paint a large work depicting a mountainous landscape with oxen, cows, sheep, figures etc., which still hangs with his heirs. At the same time he ordered a work from Jan Both, promising each 800 guilders, and an additional gift for he

2

Nicolaes Berchem and Jan Baptist Weenix

The calling of Matthew (Mathew 9:9), c. 1657

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 1058

Page 114

who had acquitted himself best. Now when these works were done and were placed next to each other, he said, Each of you has shown his diligence, and gave both a present. That is the right way to awaken ambition in artists, though now falling into disuse.

He died in the year 1683 on the 18th of February and was buried on the 23rd in the Westerkerk in Haarlem [= Amsterdam].

It would not be inappropriate for us to bring on stage his commendable contemporary JAN BOTH, who for some time competed with him for the laurels of honour on the racing track of art, followed by his brother ANDRIES.

JAN and ANDRIES BOTH, born in Utrecht (in what year I don’t know), first learned the rudiments of art from their father [= Dirk Joriaensz. Both] (who was a glass engraver) and then with Abraham Bloemaert. They travelled together (says Joachim von Sandrart) first to France and from there to Rome and made diligent use of their time. JAN applied himself to the painting of landscapes, imitating the nature of Claude Lorrain, at which he succeeded, for his reputation grew and that of Claude receded, since he made handsome landscapes but poor figures and animals, while in the meantime JAN made use of his brother, who was a commendable figure and animal painter and had taken up the handling of Pieter van Laer. They were exceptionally adept at painting, so that one saw their pieces in quantity both in Rome and in Venice (where they also lived for a long time) with art lovers and art dealers, since they were quickly painted

Page 115

and quickly sold. The majority that one sees are large pieces, and many of these depict the sun seen through the trees rising above the mountains, shining on the fields, which look naturally covered with morning dew, with everything leading into the distance discovered as if through a haze. The divisions of the day can clearly be discerned from the various tempering of the paints. One sees the dawn covering the fields with a blue veil, the bright afternoon revealing the objects clearly, and the dusk fading the green fields, trees, and terrain with its saffron-coloured glow.

Some years ago I saw a beautiful and artfully painted piece by him with the art lover Marinus de Jeude, then bailiff of the Haarlem court, which stood out from all his work in clarity, purity and naturalness and was called the testament of Both, that is to say the piece which he had left as a sample of his art to sustain his fame. This piece was more than 6 feet in height, and depicted the fable of Argus and Mercury, who were excellently painted and drawn in appropriate size. In addition the entire landscape was clear, and the green naturally fresh in colour, instead of overly burned or tanned, as one often sees by him [3].

They lived together in Italy for many years, got along well and were of great help to each other in painting and would certainly have remained there longer had not death divided them,

3

Jan Both and Nicolaes Knüpfer and Jan Baptist Weenix

Italianate landscape with Mercury and Argus, dated 1650

Munich, Bayerische Staatsgemäldesammlungen, inv./cat.nr. 140

Page 116

to the regret of the goddess of art, which is alluded to by this verse:

The goddess of art at once put on her mourning robe:

And covered with a veil her eyes, cried moist,

When she was just brought the sad rumour

That death had also felled BOTH* unexpectedly.

To find rest and escape or flee from the memory of the land which held his brother ANDRIES smothered after death had quietly crept up on him and cut off the thread of his life in the year 1650, Jan Both, the phoenix of landscape painters of his time, returned to his fatherland and native city, where he was well paid for his art and had much to do. But he did not live long after that for

Like a turtledove ever mourns

The death of her partner:

So JAN mourned over ANDRIES

His brother, torn away from him,

By the sad fate of death, which does not

Bother with mourning or grief.

I will at once mention what accident caused the demise of ANDRIES.

Joachim von Sandrart says: That he drowned in the night having wandered away from company. And the author of the book Abrégé de la Vie des peintres says on folio 429: Henrik was the landscape painter and drowned or suffocated, who being in Venice & heading for home in the night fell into a canal. Who has ever heard of Henrik Both? And consequently the reader can see what how little we can rely

--------

* Andries.

Page 117

on writers who, living abroad, have no opportunity to examine matters. That was also one of the reasons why I did not want to get involved with the description of Italian and French painters or venture outside my circle in time, but have remained in it, as the memory of the deceased is not altogether obliterated and one can receive information from descendants. Because, with things that happened long ago or far away, it is customary (as the proverb goes) to palm off turnips as if they are lemons on one another.

We would also have made a great mistake if we had followed Roger de Piles in the preceding biography had we had not been provided by more secure information, which has since caused us to reflect and decide not to rely on foreign writers. It has nevertheless happened to us at the beginning of our first volume, about which nothing is now to be done other than to recant or recall it.

On page 137 of our first volume we said about JOHANNES TORRENTIUS, following the description of De Piles: That he was imprisoned at the charge of the court of Amsterdam, for which one should read Haarlem, as does Sandrart. And on page 138. He died under torture, which Florent le Comte seems to confirm by saying that he died in terrible pain, which gave me all the more assurance that the matter was recorded according to truth. But when the description of the city of Haarlem by

Page 118

Theodorus Schrevelius came into my hands and I leafed through it, I quickly discovered the mistake committed. Most of the circumstances run alike but in two of them I slipped through emulation, which the reader will soon discover when he reads the passage below. They are Scrivelius’ own words.

JOH. TORRENTIUS was not one of the least among painters, but was the second Apelles in the painting of naked women in all sorts of arousing ways, as public whores are wont to behave. He came from Amsterdam to live in Haarlem in a house of the old Coltermans, knew how to insinuate himself into the favour of the most excellent burghers with his velvet tongue, and was everyone's friend, but in particular he knew how to flatter and court women, so that he tempted many to his house, even against the wishes of their husbands. On the street he had very stately air, always dressed in black velvet, and greeted everyone with a pleasant and commendable face, so that everyone looked up to him; but at home he daily made great show as Epicurean with drinking, eating and other pleasures, and believed in neither heaven nor hell. In one word, under the guise of a pious man, he was a tempter of youth, a seducer of women, a cheater of the people, and a wastrel of his own and other people's money. This finally got around, so that many townsmen, in whom the fear of God resided, were irritated, loathed his godless way of living and cried out that he was not worthy to live in their city.

This having come to the ears of the Magistrate of the

Page 119

city, they officially, so that the commonwealth might not suffer damage thereby, had this monster brought to prison, and after painstaking examination of his despicable way of painting, behaviour and speeches interrogated him, and when he did not want to confess to that with which he was accused, put him on the rack. But he withstood the pain stubbornly, without any confession, after which they consigned him to the house of correction for 20 years. This was in the year 1630, on the 25th of July.

When he had remained there for a long time, he was released on the recommendation of great men, including the English ambassador [= Dudley Carleton], with whom he shipped out and spent a long time in England, until he came to live in Amsterdam, where he also died.

If the painting youths are prepared to listen to good advice, they should, instead of depicting such repulsive subjects to their shame, much sooner use their brush to display mirrors of virtue

This lesson is not new, but an eager stomach also likes well-warmed spices, especially when they are refreshed with a fresh sauce.

It is not appropriate that one openly shows scandalousness, guile, and repulsive and filthy acts which are transacted in the dark or through own shame behind curtains.

The arts of painting and poetry are sisters and are both nurtured by the modest nymphs of Parnassus, whose honour is slighted by such activities. What do you think is the reason why the play about Joseph is kept out of the theatre by many?