Volume 2, page 310-319

Page 310

mentioned) and ripped it to shreds, so that afterwards I had quite a job (when Romeyn de Hooghe sought to make a print of it [1]) reassembling all the pieces and fragments recovered from the iconoclasts or bought for small sums, to make a sketch of the configuration of the work. This was because the original model for the piece was hidden away in an unknown corner at that time, whereas it now hangs in splendour in Dordrecht in a case on the wall in the house of the art-loving Mister Pompe, Lord of Oostendam [= Jacob Pompe van Meerdervoort], and shall certainly now (the storm having blown over) be kept as a lasting memorial in that family residence [2]. The daughter of the Pensionary [= Anna Elisabeth de Witt], who had been married to Mister Simon Muys van Holy, councilman of the city of Dordrecht, also has a copy of it [3].

Yet one more notable event happened to our De Baen in the mentioned year of troubles, when the French Rooster approached the Dutch lion's garden with great strides, which we would like to mention.

When the Louis XIV, the King of France, had reached Utrecht with his military forces, there arrived for our De Baen a letter signed by the Duke of Luxembourg [= François-Henri de Montmorency], then Governor of Utrecht, as well as a passe-partout signed by Commander Stoupa [= Jean-Pierre Stoppa], so that he might come to Zeist near Utrecht, to paint the King's Portrait, with the promise that he would enjoy a large payment for it, which would be paid to him in The Hague, for which two gentlemen would act as guarantors, and also that he would be conducted back without any danger. De Baen certainly felt himself honoured by this,

1

Romeyn de Hooghe after Arnold Houbraken after Jan de Baen

Portrait of Cornelis de Witt with the the deed at Chatham in the background, after August 1672

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-79.427

2

Jan de Baen

The glorification of Cornelis de Witt (1623-1672) , the Journey to Chatham in the background, c. 1670

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. A 4648

3

Jan de Baen

Allegory of Cornelis de Witt (1623-1672) as Instigator of the Victory at Chatham in 1667, c. 1670

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 454

Page 311

but in light of the times could not commit himself because of the danger of arousing malicious suspicions concerning him amongst the common people. His wife also strongly advised him against it, and not without reason, because it might happen to him as in the fable of the fox and the donkey. The latter was going to the estate of the lion, where he came across the fox, which he asked where he was headed so furtively? Do you not know (said the fox) the king of the beasts has pronounced a decree by which all horned animals are banished from his court (on pain of death)? Well cousin Fox (said the donkey), you have no horns, but ears. That's true, said the Fox: but what if he happens to say that my ears are horns, then I would also be in a fix, would I not?

His experience had shown him in those days that a bad reputation or an evil suspicion alone was enough to get one killed, so he took counsel with sensible people, among others the Ruler of Waldeck [= Georg Friedrich von Waldeck], who did assure him of a good reception and compensation but reminded him of what we described above, of falling under dark suspicion with the rash rabble in view of the times, and all the more because he was captain of the civic guard of his city quarter. So he turned down the Duke of Luxembourg, and stayed home. The King of France remembered him, however, as being the best portrait painter in the Netherlands; indeed, the King later wanted to have his Ambassador, called d'Avaux [= Jean-Antoine de Mesmes], who was charged with buying art for him, to avail himself of his advice and judgement.

He also enjoyed much honour and advantage from

Page 312

Friedrich Wilhelm, Elector of Brandenburg, whose portrait he painted several times, as also many princely persons.

Finally the mentioned Elector, in a sealed act signed the 23rd of July of 1676, chose him as upper court painter and superintendent of his art collection and art academy, and granted him an annual salary of six thousand guilders. But his wife, commendable and bourgeois by nature, had no desire to go live at the court in Berlin, so that he had to refuse the electoral eminence, who then requested one of his best pupils, for which he selected Jan van Sweel, who was far advanced in art and approached the handling of his uncle. He went there and got two thousand per year, free board, and his own stabled horse.

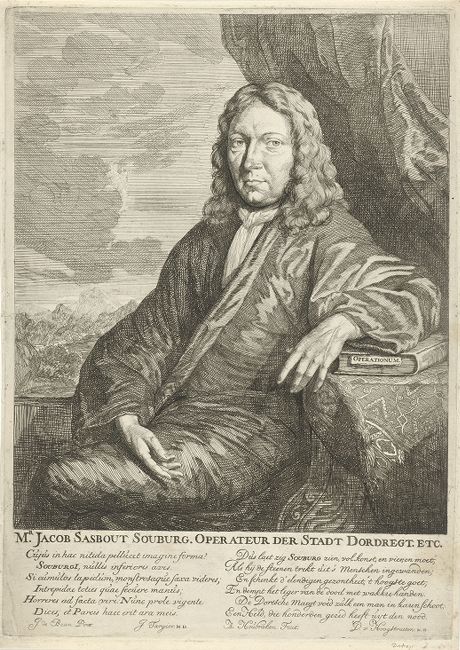

He painted Willem III, the Prince of Orange (later king of England) several times [4-5], as well as the Duke of York, James II of England [6] (when he was here in Holland) beside a great number of lesser lords and bourgeois persons too long to relate. Amongst them the portrait of my father-in-law Jakob Sasbout Souburg, surgeon [7], also appears on the list.

Amongst his great brushworks in which he especially showed his art is counted the piece with the regents of the house of correction in Amsterdam [8]. In Leiden, in the Lakenhal, there is a work with four syndics in one piece, dated 1675 [9]. In the new shooting range in The Hague there is a piece with the mayor, aldermen, confidential clerk etc., for which he received a thousand ducats [10]. Also, in Hoorn

4

Jan de Baen

Portrait of Willem III van Oranje-Nassau (1650-1702), c. 1667

Great Britain, private collection The Royal Collection, inv./cat.nr. RCIN 404779

5

Jan de Baen

Portrait of King William III (1650-1702), 1690

Kampen (place, Overijssel), Stadhuis Kampen, inv./cat.nr. 1657

6

Jan de Baen

Portrait of James II Stuart (1633-1701), later King of England, dated 1676

Private collection

7

Jan de Baen

Five regents and two regentesses of the spin and new workhouse, dated 1684

Amsterdam, Amsterdam Museum, inv./cat.nr. SA 989

8

Arnold Houbraken after Jan de Baen

Portrait of Jakob Sasbout Souburg (1637-1694), c. 1675-1694

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-1878-A-1058

9

Jan de Baen

Staalmeesters van de Lakenhal te Leiden, 1675 (dated)

Leiden, Museum De Lakenhal, inv./cat.nr. 12

10

Jan de Baen

Group portrait of the The The Hague city council of 1682; on the wall a painting of Solomon's Judgement, 1682 (dated)

The Hague, Stadhuis aan de Groenmarkt

Page 313

there are two great pieces with the governors of the East India Company in one [11] and the captain as well as the lesser administrators of the citizenry in the other [12]. But where he demonstrated his art unusually well was in the portrait of Prince Johan Maurits of Nassau-Siegen [13], who was prepared to sit as long and as often as he wanted, to which De Baen availed himself and executed the work to the outer limits of art, to the great satisfaction of the ruler and all connoisseurs. In Cleves and elsewhere he often served as company for the ruler, which made great demands of him. Before his death the ruler also left him the above mentioned artfully painted portrait of his person. To refresh this worthy memory through seeing it daily and also because this was the trial peace of the art of his brush, he did not wish to sell it as long as he lived (no matter how often requested). He also emphatically ordered his children (lying on his sick bed) not to sell it except to the court of Brandenburg. Accordingly it was not until 1702 (when the King of Prussia was in The Hague, De Baen having died that same year) that his daughter presented it to the king and sold it for four hundred rixdollars.

He made a lot of money in his day through the practice of art, but he also lived munificently off it, and all who came to visit him were welcome. A new hat (this was his expression) and one additional cask of wine per year make many good friends. He did get friends this way, but mostly pot lickers or

11

Jan de Baen

Directors of the Hoorn chamber of the VOC, 1682

Hoorn (place, North Holland), Westfries Museum, inv./cat.nr. 02000.a

12

Jan de Baen

Group portrait of the captains of the civic guard in Hoorn, dated 1686

Hoorn (place, North Holland), Westfries Museum, inv./cat.nr. 2 (cat. 1924)

13

Jan de Baen

Portrait of Johan Maurits van Nassau-Siegen (1604-1679), c. 1668-1670

The Hague, Koninklijk Kabinet van Schilderijen Mauritshuis, inv./cat.nr. 5

Page 314

table leeches, including the landscape painter Bartholomeus Appelman, who had a habit of campaigning on foreign soil for weeks on end.

One reads in Livy how Agrippa Menenius, sent by the Roman Senate to the rebellious citizens to persuade them to return, presented this fable, or parable: That the members of the human body once got into a quarrel with one another, and complained about the stomach. How the feet carried the whole body. How the hands worked, and fought. How the head was always occupied with thoughts and deliberations, and that everything that they won or obtained by this was consumed by the stomach, which did not work. We could well say (alluding to the freeloaders whom we just mentioned) that our De Baen had many stomachs, who helped consume what he gained by his ingenuity and hands. On top of this he had six children, and three more of his sister, and five of his wife's sister, both inside and outside his house, to support. They could not exist on the wind like the sturgeon, so that he had to watch his money later in life, because his lucky star already fell several years before his death.

His son JACOBUS de BAEN also practiced the art of painting, but the lamp of his life was extinguished by death in his 27th year, which caused his father great sorrow during the two years that he outlived him. We will commemorate him in his year of birth.

Now I still have to relate a remarkable and rare incident that befell our artist. Do not let it vex you, reader, if it

Page 315

turns out a little on the long side. If it were trivialities, I would be ashamed to burden you with them.

All things (says the proverb) have two handles.

This applies to the divided or differing conceptions whereby events that occur appear to elicit different emotions in the minds of people.

Appear to elicit (I say) because all events are only subject to one interpretation and the effects of the same depend on the nature of mind, and the greater or lesser dispositions for evil or good have their origin in a good or bad disposition.

The talents of art are unevenly distributed, and the one rises in height above the other like a cedar amongst shrubs. The first would be the last (when applied to the art of painting) if the one who practised the most came closest to the bull's-eye, or the target at which everyone shoots with the arrow of his cleverness. This instils additional zeal in those whose arrows fall short of the mark (if the former possess a noble spirit), and they feel spurred on to continue that practice. So should the practitioners of art also conduct themselves amongst each other, but the moment that envy arises on account of this, it is proof of a malevolent disposition, which begrudges in others what ought to be praised.

This manifests itself mostly in cowards and those who possess a low spirit, who would rather give up the pursuit of further practice to make it their job to revile those who excel, and to glower at their acclaim with crooked faces.

Page 316

It pleases us to point out using praiseworthy examples of how painters ought to behave to one another to nurture art, build her up and support her esteem. After which we will sketch in black charcoal to mirror the evil consequences that spring from envy (when people give that passion full rein).

The Three Graces [14] painted by Raphael of Urbino in Rome in the Petit Palais or small Chigi are famous as one of his best works and decorate the entryway of the mentioned Gegy or Chigi. Now the rumour spread that the Galatea [15] that he painted in one of the rooms was supposed to be incomparably more beautiful and artful. Michelangelo, keen on seeing the piece while it was still in progress but having no opportunity to do so because no one was admitted there, because they were not good friends, invented a ruse. He dressed up in farmer’s garb and hung around the door until he found an opportunity to encounter a servant who opened the door, whom he then addressed thus, in farmer’s fashion: I have heard that Raphael is painting a sea goddess in one of the rooms of this palace. I have never seen any such thing and therefore ask that I may see it once, adding to this: Then I can tell my children, coming home, that I have seen something unusual. The servant rejected him but by long persistence and tucking something in his fist he was admitted and pointed to the room. Michelangelo, finding himself alone in the room (for he had observed that at this time Raphael and his students, who were painting in that room, were having their

14

Raphael Rafaël

Cupid and The Three Graces, 1517-1518

Rome, Villa Farnesina

15

Raphael Rafaël

The Triumph of Galatea, c. 1512

Rome, Villa Farnesina

Page 317

afternoon meal) and having sniffed at everything, finds some charcoal, climbs on a chair or bench and in a round niche above the door draws with it a human head as large as life seen in foreshortening [16], and leaves the room quietly.

Rafaël, having dined and returned to the room to get back to work, sees this and asks if anyone who was in the room in his absence. The doorman said no one but only a farmer, and that he had persisted so long that he admitted him, but did not know who he was. Then I will tell you (said Raphael) who this farmer was. It was Michelangelo. For no one else can do what you see here, and pointed to the drawn raised head and then let the master of the house know what had happened.

The work on the room being thus far completed, the patron wished that this compartment be painted as well, but Rafaël refused to do so, saying: that area was so artful that no one could improve on it, that he would not turn his hand to it, but that it must remain as a worthy memorial to art. Accordingly it remains this way to this day.

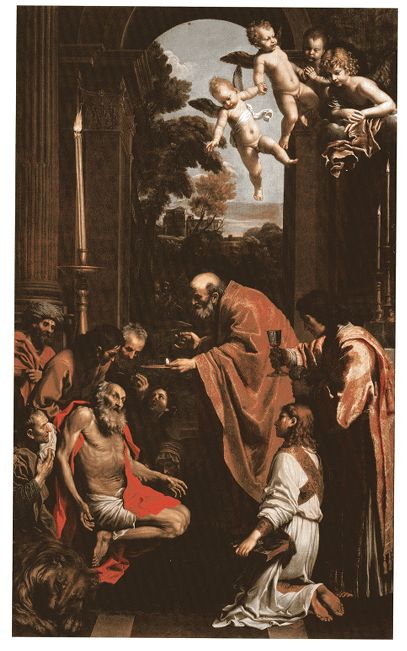

In the same way it is told of the painter Annibale Carracci that he had painted an altarpiece in the small church of St. Gregory [= San Giorgio al Celio] at the colosseum, and that two of his best students, Domenichino and Guido Reni, would also each paint a work and that the paters exacted that (with these two works completed) Carracci would paint the last touches, to which he had agreed.

15

Baldassare Peruzzi

Monochrome portrait of a young man, c. 1511

Rome, Villa Farnesina

Page 318

The first mentioned had depicted the flagellation of Christ [16] and the other St. Andrew carrying the cross [17]. Once the works were completed and to be placed, the monks insisted on the basis of their agreement with Carracci that he improve them with his artful brush where they were wanting. But he refused this, saying: that he considered these pieces to be painted divinely according to art and that he who would improve on them would have to be a greater master in art than he himself.

The great Peter Paul Rubens, when the monks did not want to pay Anthony van Dyck for the worth of his art (as we explained expansively in his place) took it himself and then paid Van Dyck to have art retain its value and cheer him up. And so the painter Jacob Adriaensz. Backer took his student Jan de Baen (as just mentioned in his biography), still being young, into his company and praised his brush work over his own. These artists thereby left examples of how one should build up art and raise artists above oppression.

If we should now place those who mean well and those who intended evil opposite each other in the balance, the latter would decidedly tip the scales.

Those who have outgrown shame strike with their nasty sting in plain view. The painter Eustache Lesueur in his time received a command to paint a dome for the Queen of France, for which he made a drawing which he handed to the queen, who was most pleased with it. But Charles Le Brun (to whom she showed

16

Domenichino

The Flagellation of St Andrew, 1608

Rome, San Gregorio Magno al Celio

17

Guido Reni

Saint Andrew being led to his martyrdom, 1609

Rome, San Gregorio Magno al Celio

Page 319

this sketch), driven by envy, said only: That it was not a job for such a man, and with that its progress was foiled and Le Sueur rejected. Some courtiers learn this from their rulers who (according to the saying of Sallust) pretend to be honest in everything that serves them and gives them advantage. But those who for appearances sake do not wish to act accordingly, or admit to it, do so covertly.

Domenichino, in Rome, painted the history of St. Jerome [18] for the priests of that order, to be placed above the great altar, but secretly incited by enviers of art, who deemed this art work unworthy of such a location, they placed it elsewhere in a corner, not withstanding that the artist often insisted that it ought to be placed where everyone could see it. This came to the attention of one of the cardinals, who was especially art-loving, who sent an impartial artist in his name to the paters to view the work and examine its virtue, who praised it to the skies, so that this cardinal made this unfairness or oppression of Domenichino his business and summoned the slanderers (having determined who they were) and forced them to explain why they had maligned the mentioned piece.

When they saw themselves forced under pressure to confess about this truthfully, they professed that if they had praised the work according to its worth, the creator would have been praised as the greatest master in Rome, and praised above them all.

See what Envy and Slander may not bring about.

18

Domenichino

The last communion of S. Jerome, dated 1614

Rome, Musei Vaticani