Volume 2, page 280-289

Page 280

never saw his equal in facility at painting, as will appear from some examples, which is why they baptized him as Mercury in the Roman painters’ bent.

Le Blon and some Netherlanders, each with his portfolio under their cloak, were drawing at the Colossos* when our Roos happened to walk by while they were arguing with each other about this or that lively ruin. In the meantime Roos’ eye fell on something that he thought worth drawing, so that (as he had not brought drawing equipment with him) he told the youngest of the company to lend him a sheet of paper and a drawing pen to sketch that lively chunk, as happened. And he made a complete drawing within the time of a half hour, so wittily and boldly drawn that it was amazing, and he gave it as a present to the one who had lent him paper and pen for the purpose. How artful this drawing was is clear from this. While they were looking over and again, an art-loving Roman happened to come by and looking at it casually, offered a pistole for it. But this did not fly as the

--------

* The round theatre, built by Vespasian. In it stood a remarkably large Colossus statue, after which the place was later called Colosseum. This was the most splendid theatre of Rome, of which today only a few remains prove its great size, which clearly show that within its encirclement 850,000 people (as the writers witness) could admire the games.

Page 281

owner wanted to keep it in remembrance of Roos and as sample of his fleet hand.

Once upon a time our Roos, who as a flighty Mercury was always undertaking or doing something here or there, stood outside Rome drawing some animals after life that were grazing in a field there. Chance would have it that the renowned Italian history painter Giacinto Brandi came by, had his coach halted and called out to him: Show me what you are making? He then asked after his name and what countryman he was, which questions he answered with great politeness.

Now I must say in passing that the Italian masters had a habit, when they encountered one or another young artist drawing in a church, palace or at some statue, they would require him to show the work, praise his zeal and point out the shortcomings and how to correct them. Sometimes they also give a piece of money to encourage him in his efforts, a practice by which they make themselves liked and esteemed by all.

Giacinto Brandi (to get back to business) took such pleasure in the draughtsmanship of Roos that he offered him admission to his house to see his art, in which he did not fail. What happened? This Brandi had a daughter who was young and comely. Roos once saw her from a distance roaming through the house and took notice of the whereabouts of her quarters. It happened one time that he came to the house while Brandi was occupied. Familiar by now to all the inhabitants of the houses, he used a pretty tale to penetrate to the courtyard, pretending

Page 282

he wished to remain there patiently until there would be an opportunity to speak to Brandi. Facing this courtyard was the room of the daughter, whom, while he was looking around, he saw standing behind the iron bars of her room and whom he greeted politely and without dawdling long gave proof of his affection by signs (he dared not risk speech). This happened repeatedly, until she also gave proof of her affection for him. No matter how secret these two lovers believed their mute courtship to be, it had been observed and tattled to the father, who denied him access to his house and his favour and, shortly thereafter, placed his daughter in a convent, saying: that he had not raised her for any animal painter.

By this Roos was deprived of the opportunity of arranging a timely means of departure with his loved one. Now good counsel was hard to come by, and his Mercurial spirit devised all sorts of aids in the laboratory of his brain-pan. For a young and beautiful girl with plenty of money was a perfect match for his plans. Thus he made it his business, bottling up that contemptible label of animal painter.

After long deliberation he thought up a fine ruse, which succeeded. He was so bold as to go the Cardinal Vicar and offer to become a member of the Catholic Faith, renouncing his religion and begging the cardinal’s favour and assistance in a certain case, which he at last revealed to his eminence. Now whether the cardinal showed himself inclined to his service so that another soul might be won, or whether Roos was able to convert him to his favour with velvet words and petitions,

Page 283

makes no difference to me. But things went so far that the Cardinal Vicar, that is, head of the Inquisition, went to speak to his Holiness Innocent XI, and put the case before him. The Pope then asked: who was the young man and who the father of the daughter, and what they both did. And when he was told that they were both painters, he said that is one of a kind, and ordered that the daughter be fetched from the convent to be married to Roos, which came to pass, since in view of the Pope’s words, the father, no matter how hard he took this, was obliged to accept it. Moreover, Roos would certainly have become friends with the father, had he not on the day after the wedding made the blunder that he later regretted. Although we believe that he did not intend things as seriously as they were taken, and that he only wished to convey that he had married her for no other reason than out of love for her, and could maintain her in her previous state with his animal paintings.

The first morning after the wedding he parted from his bride early, took all her jewels, clothes, socks, shoes, including the shift that she had on, bound it together into a bundle and had it brought to her father with the announcement: that the animal painter did not need this, that he had only desired his daughter naked. Brandi took this so poorly and it grieved him so badly that he tormented himself about it and died soon after, after having first disinherited her of his estate, which was estimated at a great sum of money.

As everything down to the clothes now

Page 284

had to be bought and made anew, the young wife had to play the part of naked truth in bed, which, had this occurred in the time of the Metamorphoses of Ovid, might easily have tempted the lustful Jupiter to join her under the covers in an altered guise.

Passing over this I must say that she encountered more changes during her married days than she was used to, for beside muddling along and poverty she was often lonely and alone, seeing that he was especially addicted to the hunting of game and his bent company, so that he was sometimes away from home for weeks and days on end without her hearing from him.

He lived in house which was a great hulk in ruin in Tivoli, outside Rome, in which wild surroundings he housed all sort of animals, large and small (to paint them) , which is why his dwelling was called Noah’s Ark by the bent. From there he often rode on horseback to Rome with a servant without having any gold and silver coins on his person and set himself to painting in some inn or another, where he then completed one or two pieces in haste (since was exceptionally adept) and sent his servants with them, still wet from the easel, through Rome to sell them, be it for a high or low price as it turned out, because he then needed money to be released with his horse from the inn, seeing that no one in Rome would vouch for him. Le Blon and others have told me that when his bent brothers saw him coming from far away they could at once see if he was impecunious or not, for if he was low

Page 285

on money and saw someone of his acquaintance coming, he crept out of their sight by some other road, but if he was flush he could approach them like a peacock and would not desist until they went to the nearest inn with him to help him consume his money. Thus he played the part of Easy come easy go.

Seeing that he painted so easily, so many works by his hand circulated in Rome that the price of his art diminished, which his servant, who was more perspicacious than he and was perhaps backed financially by his friends, exploited. Because if dealers did not wish to pay what they were worth so that he returned with the pieces, and there nevertheless had to be money, he acted as if he would bring the works to the dealers but instead brought them to a room which he had rented for the purpose, piled them up and gave his master as much money as had been offered for them. Whereby the servant later, when he was no longer in the service of his master and the price of his art had risen, made thousands.

He had a flattering brush, especially painting all animals, oxen, sheep and goats naturally and spry. And no matter how many of his works of his one sees, the arrangement of the groups is different and each has its changes, right down to the terrain and background, which is proof of his rich intellect and spirit, being more fortunate in this than the famous Jacopo Bassano, who only disposed of a limited number of figures and animals that he employed in all his art works.

It pleases us (before we draw the man’s biography to an end) to demonstrate an

Page 286

amazing sample of his fleet brush.

The imperial ambassador Georg Adam, Count of Martinitz, and General Roos, a Swede by birth and a great duellist, were in each other’s company in Rome and came to discuss the facility of our Mecury. General Roos thought it a marvel and did not want to believe it. There therefore arose between him and Count Martinitz a wager for a certain number of pistols that he would show him that the painter could prepare a piece of painting for Roos in the time that they would play a certain card game (which usually lasted a half hour). At once our painter, who was not far away, was called and asked if he would undertake this and when he answered yes, he was ordered to begin. Palette, easel and a small canvas, called Tela di Testa* by the Romans were brought to the room and Roos began to paint, but the game had not yet come to an end and our fleet Mercury already stood up and showed the completed piece as proof that he had won. In this small work there were two or three sheep or goat and half a figure painted with appropriate setting or landscape, to the amazement of the Swedish general, who had lost the wager. Martinitz took a few pistoles from the pile between his fingers and gave them to Roos for his trouble, which, quickly won, he quickly consumed.

* Tela di (Testa) A small cloth big enough for a human head to be painted on it.

Page 287

Le Blon has also told me that he saw a great piece that he estimated at 40 feet across, with all sorts of animals, up to 600 in number, and many of them life-sized, such as horses, bulls etc. in the foreground, the rest decreasing, which he painted in 16 days and that so naturally and powerfully that it was scarcely believable that such could have happened.

It would be in vain if I were to give my Dutch colleagues in art a broad report on the fluid brush, natural and powerful mixing of his paints, inventive combinations, and firm drawing that may be discerned in his work, seeing art lovers have access to the famous art cabinet of Mister Pieter de la Court van der Voort in Leiden, where a large work by him may be seen that speaks for itself better than I can express. In it an enraged Bull is depicted, attacked by a group of dogs, the pendant of which hangs in the house of the mentioned gentleman's son [= Allard de la Court], which features a grey spotted bull which tries to escape the attack of dogs by running. The painter Christoffel le Blon (being in Rome at the time) saw him paint these works.

In the year 1698 to 99 the Landgrave of Hessen-Kassel, his first patron, came to Rome and inquired after our Roos, whether he still lived and his conduct in life, and said when he heard that he had changed his religion: that I am still able to forgive him, but that he has never sent me a piece of his art as proof of his gratitude, I can never forget. Roos was informed that the Landgrave was in Rome, but

Page 288

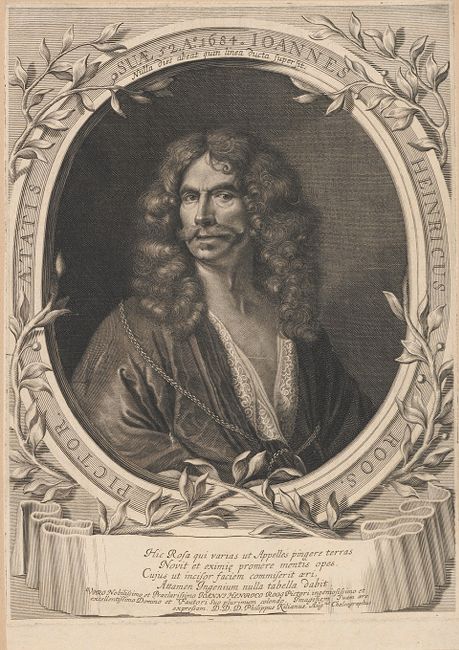

instead of going to welcome him, he did not know where to hide himself for shame. However, after repeated urging, he spoke to the Landgrave, who requested that he make something for him, with the promise to pay well for it, which he promised but did not deliver, for his mercurial spirit soon evaporating, he was counted amongst the dead by 1705. His unfortunately deceased father understood better how one ought to live in the world, for in recognition of his good instruction of art he sent his master Barend Graat, from Frankfurt, a few portrait cut by Philip Kilian [1], which we have used in Plate K.

We do not wish to neglect commemorating his uncle THEODOR ROOS, the brother of Johann Heinrich Roos, whom we have mentioned just before, born in Wesel in September of the year 1638 and as a consequence seven years younger. Unusually inclined to art he was placed with Cornelis de Bie in his twelfth year, says Joachim von Sandrart I. But here a mistake or typographic error must have crept in, seeing that Cornelis de Bie was not a painter but a confidential clerk in Lier who purely out of love of art published a book in verse about the Brabant painters. But his father Adriaen de Bie was a commendable painter and came from Rome to Brabant in the year 1623 and still lived there in the year 1660. As a consequence one should read that it was Adriaen instead of Cornelis with whom he was placed to learn art.

1

Philipp Kilian after Johann Heinrich Roos

Self portrait of Johann Heinrich Roos (1631–1685), dated 1684

Tübingen, Universität Tübingen

Page 289

After he had drawn for three months (proof of his incisive observation and great intellect that had allowed him to progress thus far on his own), his teacher put him to painting, in which he advanced so far in two year that he returned home with his parents in 1653, where he continued to practice art under the direction of his brother so far that in Mainz. Then, summoned by the Landgrave of Hessen [= Ernst von Hessen-Rheinfels-Rotenburg], they painted for three consecutive years at Rheinfels Castle, where especially our Theodoor practiced his art diligently and incessantly without letting himself be distracted by the amusements of court life.

A year after 1657, when his oldest brother had entered into the state of matrimony, our Roos left for Mannheim, where be painted the colonels of three burgher regiments with their capitains after life, which piece is still to be seen in the city hall there.

Having seen this piece Karl I Ludwig von der Pfalz gave our hard worker 20 rixdoller, which gift aroused such desire in him that he said farewell to all idle pastimes of youth and spent all his hours in the service of art. And when Elisabeth Charlotte von der Pfalz married the Philippe I, Duke of Orléans, he painted their portraits, which so pleased their highnesses that he received as gift a golden chain with a medal in which portraits of the rulers were stamped. Strassbourg and the courts of Velde, Birkenfeld, Baden and Hanau display his art. He made eight pieces in seven months