Volume 2, page 250-259

Page 250

later to avoid them. Or would it be better if out of fear of desecrating the bones of the diseased, the curious youth were blindly handed the works of famous masters as oracles and had them follow the praiseworthy with the deficient? That way no improvement in art was ever to be expected.

There are deficiencies that originate out of lack of understanding of art. There are those which creep in through error or haste and still others that arise from lack of intelligence. The second kind is easily avoided through attentiveness. The first requires more work, since to arrive at them one must climb the mount of art a little higher by diligence and effort. But the last are the mistakes which proceed from a lack of understanding. They are incurable. For just as the ignorant do not know themselves, so they have no desire to seek what they lack. From this it comes (says Baltasar Gracián) that though the pronouncements of heaven are very rare, people no longer have need of them, seeing that no one asks after them.

I do wish as the proverb goes: Not be unfriendly towards children. The deficiencies that I now censure belong less to the essence of art than to the accoutrements. Otherwise I would use a sharp-toothed currycomb, whereas I will let them pass with kind instruction.

After all everyone within whom reason resides, will praise me, especially when they have a sound understanding of the usefulness that may be born out of such reprimands. Just consider

Page 251

attentively the saying of the great Leonardo da Vinci.

It is not with the art of painting, he says, as with musical art, which dies and perishes the moment she is born, and as a result the faulty grasps perish with her. But the mistakes made in the arts of drawing and painting last a long time, to the revelation of the master’s ignorance for the rest of life.

The oft-mentioned Philips Angel II , after he has especially praised a scene painted by Jan Lievens for its inventive finds and attributes and has said that such unusual specifics are allowed and highly praiseworthy when a painter attempts them, continues as follows: This spirit also revealed its marvellous legacy by depicting the history of Bathsheba, about which we read in 2 Samuel 11, that David, after he had seen Bathsheba bathing from his roof, at once sent a messenger to fetch her, without further discussion. Thus this widely renowned spirit had striking ideas concerning the enhancement of his work: First, that this messenger must undoubtedly have been an old procuress, who is generally used for this purpose and who must have conveyed this message not just orally but also in a letter. In this he again reveals the sweet ruminations that he had upon this matter by having a blush of honourable shame alight on the cheeks of Bathsheba upon the reading of this love letter. In addition he painted Cupid in the air, not with a steel shaft but with a flaming arrow from which thin smoke arose, so that one saw his chubby legs

Page 252

quivering, aiming at that naked beauty to inflame her bosom to reciprocating love.

These additions are inventive enough in conception and well enough express the way or roundabout stratagem of a lecher to reaching his goal with the inclusion of a procuress as well as with the emblem of winged Love, the originator of passions.

Our writer praises this, and attaches his seal of approval to it, but this friend strikes out (as the saying goes) with respect to this being a Biblical history, with which painters are allowed less freedom than with profane histories and fables. Moreover, there is no trace of evidence to arrive at the decision that King David would have conveyed his burning passion for Bathsheba through an old procuress, as it would then have been left to her to decide whether to do it or not to do it. It also conflicts with the greatness of a ruler to take common roads; they merely command and it happens. It is moreover inconceivable that the king would have revealed the target of his missive to some court messenger, much less to an old woman (who can keep silent only about things they don’t know). We also wish to think the advantage of that anointed head that less time elapsed with respect to this affair than would otherwise have been the case, but that he had her fetched at once and that when she pleased him as much from nearby as far away, he transgressed against the Godly law in the heat of his rash passion. Attributes are an essential enhancement and serve most importantly

Page 253

to clarify the essence of a scene and make it comprehensible for the spectator. For just as the correct placement of commas and periods determines the correct meaning of things, so that when one reads a book one at once understands what it means and says what one reads, so on the contrary the punctuation when incorrectly placed through lack of attention or incompetence, not only lead to obscurity and confusion about the meaning of the sentence, but even make things totally incorrect and incomprehensible, so that we do not know what to make of them or estimate what the writer intends with them. For instance, in a sound sentence I read according to truth and in a good sense: Most people deserve not, good is God. If, now, the (,) is badly placed, after deserve instead of not, then it is not only contrary to truth but also blasphemy. And I do not know what to think about what I read. So it is also the case with respect to art when attributes are not appropriate or properly introduced.

Once more. The attributes are a necessary enhancement when they are appropriate to the depiction. Just as margin notations serve to make the essentials stated in the text known at once, so the enhancements or attributes serve to make known what is depicted sooner and at once, instead of obscuring them with an invention, as we saw in the last example.

All those who rightly understand the saying: A ship on the sand is a beacon in sea, will not disapprove or our reprimand but praise it, discerning that our digression provides the painting youth

Page 254

with a pilot to help them avoid such reefs with care.

The wise men of old have introduced a remarkable saying which goes: It is better not to do something than to do it badly. And the following story applies to this. My master Samuel van Hoogstraten had as a habit that he had his students make a weekly sketch in their own time of some historic incident (for which he supplied the subject). It happened that I showed him a working sketch for a scriptural subject, in which I had filled out the work with some accessories as embellishment, thinking that I had really gone out of my way with this. But my trousers were not as smart-looking as I had imagined, for he first asked (pointing at the attribute) what is that supposed to mean? I answered, I did that just because: whereupon he said to me, one must not do things just because, but have a reason for everything one does, why one did it, or else not do it. Thus, instead of a Bon, I got a masterful scratch.

Andries Pels teaches precisely the same basic lesson to playwrights on page 47 of his Gebruik én misbruik des toneels, which we apply to painters, as we will do from now on where it suits us instead of at the end of our book, as we have promised. He said:

Far be it from me, then, not to covet embellishments;

I love them, but above all I love, thanks to the favour

Of the Muses, material and compositions based on art.

Page 255

Other than that, if they fit in, you may help yourself

To clothes, to theatre, artifice, and machines

At their most exotic and priceless;

But I advise you thus, if the embellishment

Should compete with art, that you leave it out.

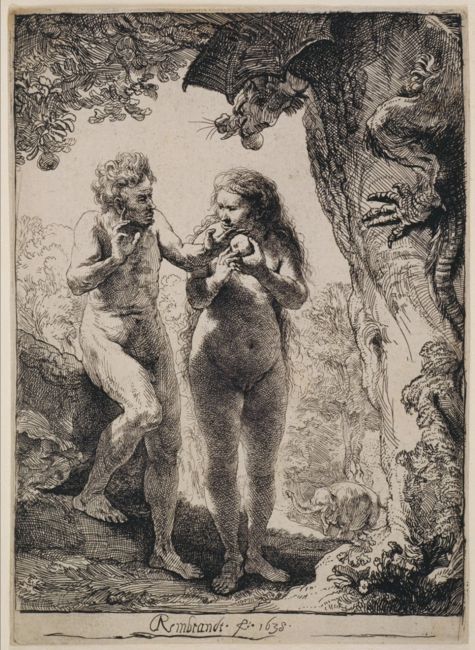

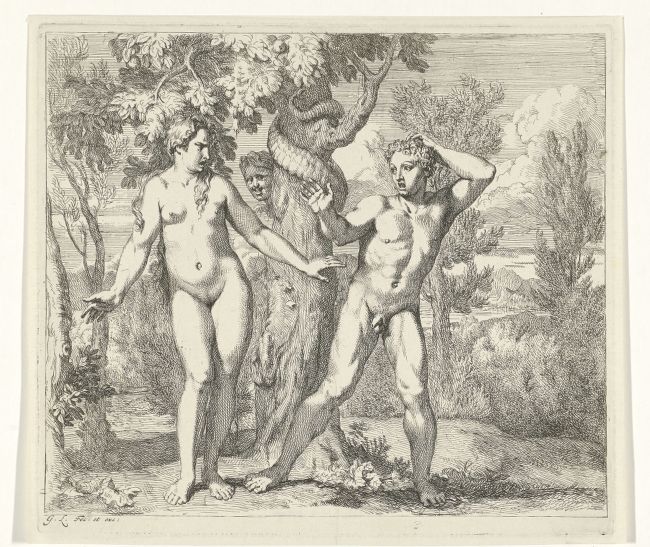

To continue, Hoogstraten was an exceptionally competent man to drill his students in the essentials of art, but tolerated not the smallest freedom that deviated from the fixed rules of art. If it happened that one or the other deliberately added something to the historical text, thinking to demonstrate his intellect by this, he was at once taught: That one should always strive to show truths; or that one should otherwise help bolster and transmit the fixed concepts. He looked at something in which they had followed Rembrandt and Gerard de Lairesse. And do you want to know what, reader? It was the depiction of the snake of paradise, which the first mentioned painter had depicted contrary to the letter of a text, as the decorated dragons in Ovid’s Metamorphoses [1]. The second artist depicted a miscreant with a woman's face [2]. What reason De Lairesse may have had for this does not excuse it. Yes, it surprised me that a shining beacon in art should deliberately have committed such a breach of the Scripture, more than with Rembrandt, of whom it is known that he bound himself by no rules of art (no matter how widely approved), but took his own pleasure for rule. That is why the excellent poet Andries Pels, in his Gebruik en misbruik des tooneels, says of him:

1

Rembrandt

Adam and Eve, dated 1638

Frankfurt am Main, Städel Museum, inv./cat.nr. 5762 D

2

Gerard de Lairesse

The Fall of Man, 1665

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-46.747

Page 256

What a shame it is for art, that so excellent

A hand, did not better, of its native gift

Avail itself! Who would have surpassed him in painting?

Oh well! the nobler the spirit, the more it will run wild

If he ties himself to no law, or string of rules;

But wants to learn everything from his own experience

He who will not follow proven guidance can easily stray, and he who despises it through stiff-necked conceit, never achieves perfection. That is why Baltasar Gracián (here to the point) has said: some will become wise if they did not believe they were. Thus I want to address the youthful painter with the words of the Preacher, where he says: In case you lend an ear you will learn and in case you take pleasure in listening, you will become wise.

All those who intend to depict histories do best to chose ones for which he judges that everyone who has done some reading will at once know and recognize at first sight what they depict, without people having to guess fearfully or the spectator of the scenes long kept in the dark, which only happens with respect to such subjects when the clear indications are mixed up or changed and therefore result in obscurity. For instance, I see a group of people fleeing with some domestic animals. What am I to make of that or apply to it? But when I see depicted a group of blacksmiths who are driven out of the city along with groups of roosters, it will

Page 257

at once come to mind upon seeing the same that the Sybarites, a people surrendered to all luxury and laziness drove the roosters along with the smiths out of the city, so that their indulgent sleep might not be disturbed. And this beside me is known to all those who have read Petrus Francius’ Lofreden van den Haan.

Similarly when one sees depicted a Greek practice school which features a man with a plucked rooster, everyone who has read the farcical play of Diogenes will at once see that the man with the rooster represents Diogenes, who scoffed at an oration by Plato with this.

It may be that the histories which one chooses to depict carry with them their own recognizable signs and supplements. It may be that that they have to be added from elsewhere, but they must always be essential to the subject matter. Mister Gerard van Loon says most wisely on page 101 of his Inleiding tot de penningkunde: That nothing must be placed as subsidiary ornament that is not related to the intended aim and is not essential to it. Just as no personages should be tolerated onstage who do not truly contribute to the development of the play. And that play which is deemed most perfect in this respect is one in which all personages brought on stage are of genuine importance to the denouement of the matter on display. And thus all additions which, instead of adding lustre, serve to extinguish the simple grandeur and the essential etc., and finally: The subsidiary decoration must make the main actors so recognizable that one is not necessitated to write about them, this is so and so, etc.

Page 258

As did the dauber Guiliam van den Brande, about whom they still sing in Brabant:

Mister Guiliam van den Brande,

Great of girth but slight of understanding,

Painted at one and the same time,

A hare and a preying greyhound;

And to show that he was in charge,

He wrote above it, this is the dog and that is the hare.

We could contribute more examples of this kind if we did not wish to limit the length of our digressions. He who is observant will be able to tell from the samples what the nature of the fabric may be.

Now BENJAMIN von BLOCK, born in Lübeck in 1631, has his turn. He was the son of Daniel Block, whom we mentioned in the year 1580. The reason we had for this was, to wit, because the father was born in the Bishopric of Utrecht, which also requires that we commemorate the son, all the more because like a new Aeneas, he rescued his father and mother from the fire started by the enraged soldiery in Schwerin.

Robbed of nearly everything he owned by the fire, Daniel Block left behind in poverty four sons, of which three took refuge in art, being Emanuel, Adolph, and our Benjamin.

It seems to me that Adolf Frederick I, Duke of Mecklenburg-Schwerin, taking pity on the family because of this mishap, did the family a service and took our Benjamin

Page 265 [= 259]

under his supervision and care.

The first trial piece of his art and intellect that he made was a portrait of the Duke, full length, with the pen, which amazed all who saw it. This was in the year 1647 and shortly thereafter he painted in living colour the entire court household of Saxony. He then painted various scenes and altarpieces for Count Ferenc III. Nádasdy-Fogáras in Hungary, which were particularly praised.

In the year 1659 he travelled to Italy with letters of recommendation from the mentioned count, where he gained access to the best art cabinets. After he had spent some years in Venice, Florence and Rome practicing art and had painted many important people, including father Athanasius Kircher, he returned to Germany and in 1664 married Anna Kathrina, daughter of the famous Johann Thomas Fischer of Nuremberg.

This ANNA KATHARINA BLOCK excelled at the painting of flowers both in oils and water paints and had instructed the ruler’s wife and daughters in this before her marriage.

Joachim von Sandrart I witnesses that he had the luck that she was painted twice by him and that she was still alive when he wrote his Book of Painters.

The steep mountain of art, which is so difficult for some to climb that the sweat breaks out before they get half way (per aspera ad ardua,