Volume 2, page 130-139

Page 130

also died of consumption in The Hague. His portrait appears in Plate F 1.

What poltergeist so bewitched the eyes of art experts that they formerly mistook the brushwork of Paulus Potter for common art? Or did they have sight at that time, and are we who profess so much respect for it now blind? What sayeth thou reader?

It seems that all things under the moon are subject to change. The earthly kingdom, however firmly the base of its construction may be moulded, waxes and wanes. Lands that were formerly populated areas have turned into wilderness. Others having come out of nothing have grown into objects of admiration. That is also the case with art and learning. In olden times Greece was the advanced school of scholarship and the arts. There she revealed herself, just as the pleasant dawn displays her glorious being as she blushes over the horizon. There, like the sun, she ascended on the wings of rich and liberal rewards to the zenith of the meridian. From there the goddess of art placed painting first in Italy, and then (so as not to create envy) also in other lands and kingdoms, including the Netherlands. There, sometimes more, sometimes less, painting has always flourished in splendour, but never more beautifully than in the interval between the years 1560 and 1660.

It pleases me to compile a list of alert men who flowered between the life span of one of these artists, and present it below.

Page 131

Abraham Bloemaert,

Tobias Verhaecht.

Michiel van Mierevelt.

Paulus Moreelse.

Roelant Savery.

Peter Paul Rubens.

Hendrick van Balen I.

Jacob Jordaens I.

Frans Snijders.

Daniël Seghers.

Jan Brueghel I.

Frans Hals I.

Cornelis van Poelenburch.

Anthony van Dyck.

Jan Davidsz. de Heem.

Gerard van Honthorst.

Jan Porcellis.

Palamedes Palamedesz. I.

Rembrandt.

Emanuel de Witte.

Erasmus Quellinus II.

Jan Lievens.

Ferdinand Bol.

Adriaen Brouwer..

Jacob Adriaensz. Backer.

Herman Saftleven.

David Teniers II.

Adriaen van Ostade.

Cornelis Bega.

Gerard Dou.

Gabriel Metsu.

Bartholomeus van der Helst.

Nicolaes van Helt Stockade.

Bartholomeus Breenbergh.

Ludolf Bakhuizen.

Pieter van Laer.

Gerard ter Borch II

Hans Jordaens IV.

Nicolaes Berchem.

Thomas Wijck.

Abraham Genoels II.

Govert Flinck.

Peter Lely.

Hendrick Verschuring.

Otto Marseus van Schrieck.

Willem van Aelst.

Philips Koninck.

Willem Doudijns.

Philips Wouwerman.

Jan Both.

Adam Pijnacker.

Melchior d' Hondecoeter

Jan Baptist Weenix.

Frans van Mieris I.

David Beck.

Caspar Netscher.

Jacob van der Does I.

Jan Steen.

Johannes Lingelbach.

Willem van de Velde I.

Paulus Potter.

and still others

Page 132

The sun shone on all of these painters (the one earlier, the other later in time span) in one day, for Abraham Bloemaert, who is the first on the roll, born in 1564, outlived Paulus Potter, who died in the year 1654. And the art lovers have also been able to amuse themselves by the sight of such a variety of art works.

Just consider what a great number of lesser lights appeared on the Dutch firmament of art in that ample interval, and how few and far between they are today. Yes, how scarce are they that stand out like the full moon from the stars. Thus one can only regret more and more the number of empty places in Pictura's training school. And with reason, when one sees that diverse parts of art have been torn away and have fallen into the grave along with their praiseworthy practitioners, with no hope that they shall arise again with heightened beauty. Who has arisen in painting the sea and ships since the death of Jan Porcellis, Ludolf Bakhuizen, Willem van de Velde I and Allaert van Everdingen? Who in the painting of livestock since the death of Nicolaes Berchem, Paulus Potter, Adriaen van de Velde and Jacob van der Does I? Who in the painting of horses since the death of Philips Wouwerman and Herman van Lin? Who in the rendering of peasant and military Life since the death of Adriaen Brouwer, Adriaen van Ostade, Cornelis Bega and David Teniers II? Who in the painting of churches and buildings since the death of Emanuel de Witte, Jan van der Heyden and the Berckheydes [Job Berckheyde and Gerrit Berckheyde]? Who is their equal or superior? Good young painters, this must spur you on to help build Pictura's school of art with greater zeal. Do many parts of art miss their practitioners, and is the number of art practitioners

Page 133

not as numerous as before, what council? You now again have some who, having climbed to the highest step of Art, surpass their forerunners as far as these outstripped the first inventors of art in power and beauty, about which this verse by Arnold Nachtegaal applies:

The art of painting now flowers more beautiful than before:

Than when a mere maiden* by an outline alone,

Had her acquire the title of immortality:

Now she is supported by a rich treasure of paints,

Granted her by Nature; in which she even catches up;

So far that she almost pays us with its radiance.

We have seen that a large number of beacons of art illuminated the Netherlands in a compass of fewer than 100 years, and that the number is now so small that one can find no practitioners in various aspects of art. Should someone ask me what was the reason, I

--------

* Maiden. The name of the daughter of the potter Dibutades. In love with a youth she traced the exterior of the shadow of his being with a candle, which turned sideways, stood on a wall, so that that she would always have him before her eyes and in her thoughts. Pliny relates this in the 12th chapter of his 34th book, where he further says: that by often copying that outline she came so far that she could do it without the object, with the mental image, and then later on she also undertook to depict other beings from memory with a recognizable outline, and thus founded the beginnings of art.

Page 134

would ask it of him, because I am ashamed to say.

It seems to me that the situation of art at the time of Petronius was even as now, for after he has indicated that the art of painting increased as long as the generosity and rich reward from the great cultivated the effort of the ambitious to achieve an immortal name (knowing that if they could reach it, they would not lack for any profit), but that on the contrary it once more began to decline as soon as avarice gained the upper hand and there was almost no one who protected art. He introduces by a nice way of writing a sensible man whom he asks after the cause of the decline. This will answer it. Cupidity (he says) brought about the change. The free arts once flowered as long as true virtue was valued. Therefore people also sought all kinds of art, not wanting that anything that might be advantageous to their descendants might remain undiscovered. And a little further on. We on the contrary, reclining drunk by wine and other pleasures, don’t have the heart to stand behind knowledge of past arts. And since it comes easier to chide than emulate antiquity, it happens that we only seek to learn vanity and implant it in others. Do not therefore be surprised that we have lost the art of painting, seeing that there is a clump of gold in the eye of all the gods which seems much more beautiful to people than what Apelles and Phidias have ever made.

It is a little coarsely formulated. Andries Pels, in his

Page 135

translation of Horace, has painted the decline of the poetic arts with a softer brush, which we apply to the art of painting. And it comes down to this, that lovers, nurturers and supporters of the arts, who, according to the saying of Gracián, may be compared to the wind, and the painters to flour mills, which are kept grinding by the former, being so small in number, die out from time to time, and no new ones are nurtured: That the children of people of means are denied the practice of art and the sciences, the ground from which the love and inclination to the same, and finally competence, are born, on the contrary now have no inkling of them. That is why the mentioned Pels finds reason to ask:

But in what is the youth of Holland instructed?

Instead of in reading books full of wisdom,

She learns the difference between three fifths, and five eighths

Percent, and to who can calculate this, well done,

Calls man and maid out loud; it is the dearest of my children,

Says father: for he will not allow what is his to diminish;

He knows precisely how to draw up the reckoning of interest

And discount, relying on discount.

But do they expect to gain from that corrosion and concern for making money

Once it has eaten its way into, and spread throughout the senses,

That someone could possibly live on through his art work

Many a year or century after his death? Far from it.

In olden days it went differently. The Egyptians

Page 136

so greatly esteemed art that even the most powerful ones had their children practice it continuously. The Greeks did the same. There was even a law that no one was allowed to turn to painting unless they were of a freeborn and honest family. The wise Solon, seeing that the inhabitants of Athens, who were living in peace at the time, declined more and more into idleness, instituted a law that no son would be made to maintain a father who had raised him in artistic ignorance.

Since the opposite is now becoming common, one need not be amazed that the number of those who esteem art and her practitioners is becoming so small. It appears, says Sidonius Apollinaris, as if by a natural deficiency in the hearts of people is imprinted that those who do not understand the arts are also little concerned about artists. Which is why Willem Goeree said quite nicely in this connection, It is unlikely that someone, having no liking for the fruit, would hold the tree in honour. With this we want to end and lead the reader to the biographies of the following painters.

Here we let follow the unfortunate HERCULES SEGERS, whose time of birth we do not know. But because Samuel van Hoogstraten mentions in his Calliope that he flowered, or sooner withered, in his first green years, it seems fitting to us to bring him onstage before the mentioned Hoogstraten.

He was a man of good understanding and judgement, rich in ideas and plentiful in a variety of

Page 137

subjects that he incorporated in his landscapes, so that in the spacious prospects whole regions with villages and hamlets appear. He was also inventive in the embellishment of mountains and cliffs, as may be seen in his paintings and prints. But it seemed as if he was born under a disastrous planet, because though he strove with incomparable diligence, he was not able to surmount his misfortune. He had to see to his grief that others, who possessed less art, cantered ahead of him, while his wings were tied by his sad fate with the bonds of poverty. By a clever discovery he made possible the printing of landscapes in paint on cloth, but the cloths found no buyers, even though he was able to offer them for a small sum. That is why his wife complained that he ruined all the linen that was in the house and that this did not yield enough to allow her to replace it, and thus he fell into the direst poverty with his family. On the other hand, he was grieved to see that his prints were used by the baskets-full in stores selling greasy wares, to wrap butter and soap.

Finally he made a last plate, in which he invested his greatest effort, and offered it for little money to an art seller in Amsterdam, but the latter was not interested, saying that his works were not in demand. Yes, even though he explained to the dealer that after his death every impression would be worth more than he demanded for the plate, the dealer was hardly willing to pay as much as the copper had cost Hercules. Thus he took the plate back home with him and after he

Page 138

had pulled some impressions, cut it into pieces. The miserable Hercules took such things so much to heart that, being saddened and altogether desperate, he sought to drown his sadness in wine, and one evening, being more drunk than usual, he came home, fell down the stairs, and died.

Hoogstraten observes that it came to pass as Hercules had predicted, because people later paid sixteen ducats for each print, and even then it was a stroke of luck to obtain an impression. What can I say? He who has Fortune as stepmother is in real trouble, and it has happened more often that those who sowed with diligence never got to reap the harvest.

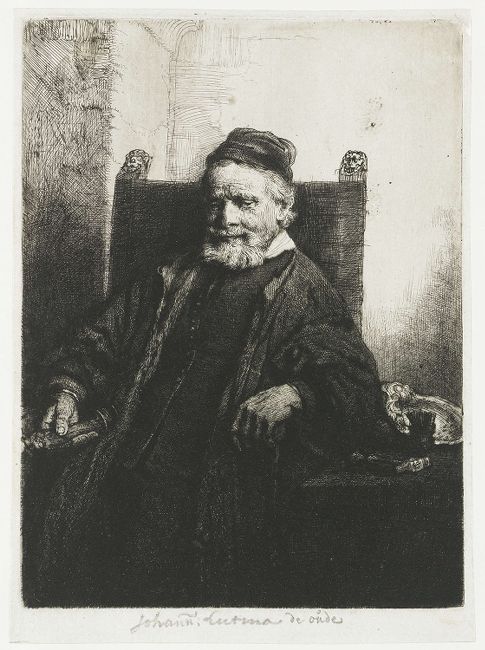

There are many such instances about which one could compose dirges too sad to sing or read. But it does not please us to adduce them. The world, it would appear, has a nature like pigs which, when one attempts to pull them forward by the ears, walk backwards. Did it not happen to Pietro Testa as with the mentioned Hercules Segers? Did he not see to his heartache that when someone bought groceries, his prints or a piece of the same were turned into a cornet in which to bag the wares? Did he not walk about Rome with his prints tucked under his cloak to sell them? The old Johannes Lutma, known for his portrait etched by Rembrandt [1], admits that once, being in Rome, he bought various works from Testa costing one ducat. And I have myself later paid 2 ducats for each of the large prints and for a small print called The Entrails Winder [2].

1

Rembrandt

Portrait of Johannes Lutma I (1584-1669), 1656

Amsterdam, Rijksprentenkabinet, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-550

2

Pietro Testa

Martyrdom of Saint Erasmus, c. 1630-1631

Amsterdam, Rijksmuseum, inv./cat.nr. RP-P-OB-38.241

Page 139

And what was the reason? People wanted them when they had become hard to come by and the maker had drowned himself in the Tiber out of dispiritedness.

Franciscus Heerman relates in his Guldene annotatien that Albrecht Dürer arrived in a certain city with Emperor Maximilian, where the Emperor showed him an artfully painted scene and asked him what he thought of it. He forgot out of amazement to talk about it, and even more when he was told: The man who painted this piece died of poverty in the poor house. To which the saying: That art at times goes begging for bread, is applicable.

Which is why an unhappy artist said accordingly: Who knows if I had learned hat making, whether nature (to foil me in everything) would not have created mankind without heads.

He is followed by

JAN van KESSEL I, born in Antwerp in the year 1625. This individual (everyone follows his own natural inclination) had concentrated on the painting of all sorts of flowers which gentle nature brings forth as well as featherless animals, the bottomless sea, and small land creatures, as detailed, skilful and precise as Jan Brueghel could have done. Cornelis de Bie says in praise of his art of the brush that he has

Managed to express life and nature thus,

(Since art can truly deceive) one would want to pick them,

So witty, beautiful and fresh every flower stands in bloom,

Executed most powerfully, and carries Van Kessel’s fame.