Volume 1, page 280-289

Page 280

At the time he also got started on his book, the Teutsche Academie, which kept him busy into his old age.

In 1672 (his wife having died) he left Augsburg and went to live in Nuremberg and on the 5th of November of that same year married Esther Barbara, daughter of councilman Wilhelm Bloemart.

The most important content of his books, published in the Latin and German languages as we have mentioned, concerns the lives of the painters, in which he followed Vasari and Ridolfi with respect to the Italians, or else Karel van Mander in his general arrangement and order. Since he had contact with many painters in his day, he described their lives and artworks, adding to these sources and thus increasing the number greatly. This useful and laudable work,

--------

* But the plausibility of this story was satisfactorily refuted by Pieter Rabus, who made a marginal note in the mentioned book by Sulpicius, by showing that just as those to be crucified carried their crosses to Golgotha, the crosses with the dead bodies were taken away. And assume they were not taken away but left lying about, and people continued to mete out such punishment for 300 years until Constantine, how then is it possible that there were only three crosses to be found under the rubble of the mountain? But should anyone want to believe this, he can do this without argument provided he can accept that I do not believe it, which quarrels with reason and reasonableness; seeing I do not know that anyone is permitted the right to rule over another’s understanding and even less to damn his fellow man over a differing concept, as Cornelis de Bie does on p. 269 of his Het gulden Cabinet in such an instance.

He who wishes to know more about this material, look to Antonius Bynaeus, Gekruisten Christus, Chapter XVII, p. 484 and Willem Goeree on p. 401 of his De kerklijke en weereldlijke historien.

Page 281

with all that appertains to it, including the multitude of plates, is enough by itself to include his name amongst memorable men.

What work, effort and diligence,

And research that a writer

Always has to do, no one knows:

But he who takes it on himself.

His last brushworks (as proof that his judgment and diligence for art had not declined with the years) are especially praised by his biographer in the Latin edition.

These were a depiction of the last hour of Christ’s dying, in which were shown Mary, the mother of the Lord, John and Longinus*

--------

* Longinus was used by the Romans as a name, as is clear from Velius Longinus Graminaticus and Dionisius Longinus Rhetor. It is likely (says Bynaeus) that the invention of Longinus found its origins in an old Greek word which means the sharp edge of a lance, spear or spike, as this word is used by Xenophon, Strabo and others. Or else it came from the meaning of tall, since (as with us) the tallest individuals were selected for the host of spear carriers. And the opinions of the evangelists are incorrect, who here invent a Longinus who, with poor sight, is healed by the blood which sprayed from the side of Christ, and later died as martyr to the Christian faith. While they all say that one of the soldiers pierced his side etc. and that specifically from the meaning of the Greek word, one of the foot soldiers.

In the Persian Gospel of Xaverius and in the Bohemian translation one reads that it was a horseman. But this misconception arose because the ancients, misled by ignorance and incorrect images, believed the crosses to have been much taller than was later established by research. About which we spoke on page 194 above.

Page 282

on bended knees. There was also a Last Judgment, to which he laid his last hand in his seventy-seventh year, and shortly thereafter moved out of this world.

Just as the faces of people differ from others in recognizable features, so also do their nature and inclination differ insofar as one has more or less control over his passions, and that is even more the case when the passions are not only given free reign but are also flattered in their nature: in which respect

EMANUEL de WITTE stood out, who as a second Diogenes the Cynic ruffled the feathers of everyone, and who like Momus mocked and slandered the deeds of one and all.

He was born in Alkmaar in the year 1607. His father was a schoolmaster, practised in geometry and a good speaker, which science Emanuel practised in his youth, which is why he had a better than average understanding of rhetoric, but for that reason also often created arguments and unrest in company, especially when subjects from the Bible were discussed, not hesitating to controvert those kinds of addresses and exposing the facts to doubt, saying: that by his fifteenth year, the scales had fallen from his eyes. And were it not that the commendable art that he possessed demanded it, his way of life would not have tempted us to grant him a place among the artists. Incidentally, he was not alone in this; we have discovered more scabrous sheep in the flock. His worthy art of the brush

Page 283

must serve as an example for emulation, but his way of life for revulsion and abhorrence.

He studied art in Delft with Evert van Aelst, of whom we have spoken on page 228. When he understood the rudiments of art, he practiced the painting of figures, histories and portraits on his own. The portrait of the wife [= Grietje Claesdr Klock] of Jurriaan van Streek painted by him may still be seen with the latter’s son. But he later moved with all of his family to Amsterdam and to the painting of churches, in which no one was his equal with respect to orderly architecture, clever choice of lighting and well-made figures. He drew the insides of most churches within Amsterdam in various ways after life, with pulpit, organ, seating, gravestones and other decorations, so that they may be identified. With some he showed a sermon, in others when the people arrive at the church, each in his customary dress.

The most important of his artworks was a view of the choir and that part of the Nieuwe Kerk where the tomb, or marble cenotaph of Admiral Michiel de Ruyter stands. This piece was commissioned from him for a substantial sum of money by Jonker Engel de Ruyter, but he died before it was finished. The preacher Bernardus Somer, who was married to the daughter of the admiral, not being knowledgeable about paintings, offered our Emanuel 200 and finally 300 guilders for them, but he stubbornly insisted on his right to his arranged deal and called the

Page 284

preacher everything that was nasty, who kept him waiting so long for the money that in anger he took his knife (even though he did not have a nickel in his pocket) and cut the piece to threads. It is only a small failing (a wise man said) if your actions are unpolished and yet that is enough to make everyone dislike you. By contrast, friendliness is agreeable to one and all.

His commendable art often made him good friends, but he was able (according to the Spanish saying) to help himself to them only until he no longer needed them. In his time two works for the King of Denmark were commissioned from him. The time that they should have been done having long passed, the consul himself came to check on them, saying that his king was dissatisfied, at whom he growled with a surly head: If the king of the oxen did not desire these pieces, he could sell them to someone else. Thus his unbridled tongue turned friends into enemies and even the artists gave him the cold shoulder. He spoke of all their work with contempt. He compared the paintings of Gerard de Lairesse to the Prinsenvlag, yes the best art was not safe from denigration.

It happened late one evening that De Lairesse arrived at the inn where De Witte sat, took a piece of chalk and drew some lines on the table to defy De Witte, who was accustomed to brag about his geometry. De Witte, who was not one to put up with such an affront for long, sketched in chalk a drawing of a canon on the table, with which he said that De Lairesse's nose had been shot off. Which De Lairesse took badly, and Emanuel did not make his escape

Page 285

unharmed. Early in the morning, at dawn, one of his acquaintances met him, who recognized him by his injuries sooner than by his appearance, as he had two black eyes, a swollen nose, and various scratches on his face. This acquaintance said to him: how now father de Witte! how came you to be so ravaged, and where are you off to so early? He received in answer, see, they did the underpainting for this deformed portrait last night in the dark, and I am going back there to have it finished by daylight.

It seems that De Witte lived by the wrong saying, The least peace is best. What need was there for him to fire off so sharp an answer at De Lairesse, as the allusion had no basis in truth? For the sickness of Venus had not recreated his nose so grotesquely, but he had been born with it, as I learned from his portrait, painted by himself when he was 17 years old.

When he then got eyes too late (as people say of moles) and saw that fortune had turned her back on him, that everyone was weary of him, and that he was seen as a stranger in his own land, looked at askance and fallen into poverty, he became dispirited with himself, especially when his landlord sometimes began to bother him for payment of debt, with reproaches that he was himself the cause of his plight and that if he had been willing to listen to advice, this could have been avoided.

We could describe more samples of his lifestyle. But they would only prove his recalcitrant nature like the preceding ones. One example I must still adduce, which is said to be among the most polite responses that anyone

Page 286

encountered from him. A certain young artist named Janssens had painted a piece which he thought to have been the best that he had made. He therefore requested that De Witte, as old and experienced master, come and see it, in the expectation that he would praise his diligence, point out shortcomings and give him courage to continue. When it was placed before him and asked what he thought of it, De Witt answered: I think you must be a contented man since such trifles please you, and left.

Just as his way of life differed from all others, so he also differed from others in his way of dying, for as reason teaches each of us that we enter the world without volition or effort, and that no one has been granted the option or right to put an end to this life, but that this depends on the pleasure of the Creator. He appears to have sinned in this respect, as is apparent from the events that occurred at that time, as from the witnesses who watched the conclusion.

I have mentioned the disputes between him and his landlord. It occurred in the last evening of his life that hard words passed between them, so that the landlord swore a dire oath that he no longer wanted him under his roof. Whereupon he got up, and said: That he had already seen to it or invented a means so that he would not say this a second time, and went out the door. Two of the company who were present there, seeing that De Witte looked unusually despondent, followed him from afar to see where he

Page 287

might end up, but lost him near the Korsjes Bridge because of the dark. That same evening a strong frost set in, and the ice remained on the water for eleven weeks, during which time no one knew where he had gone. Then, when the ice broke, he was discovered at the Haarlem locks. He was fished out and people discovered that he had a rope around his neck, from which it was concluded that he sought to hang himself on the railing at the privy of the Korsjesbrug but that the rope had broken so that he drowned.

They brought his corpse to the hospital and from there to the plague house cemetery on the Overtoomseweg, where he was buried in 1692, at the age of 85 years.

When an artist edifies by his way of life and at the same time amuses the eyes with the depictions of his brush, and uplifts the attention through worthy reflections on subjects that are instructive and edifying, then amusement and usefulness are paired.

Sculptures and pictures are books for laymen says the conciliary pronouncement, but they must also play the part. A playful feast of Bacchus, where one sees the soused satyrs lustfully chasing the field nymphs to rob them of the veil that covers their nudity, or stick their heads under the shift out of lewdness, no matter how artfully depicted, would give little cause for devout thoughts.

PIETER van der WILLIGEN of Bergen of Zoom paid attention to what is most praiseworthy. In his scenes he depicted allegories and images of the vanity of worldly treasures, the

Page 288

transience of human life and the unknown but certain moment of death. One must truly say of such images as signs of mortality:

Each is a herald of death, who says;

Remember oh man that once your lustre.

Your beauty, fame and splendour,

Will be led into the grave

And covered by a tombstone in the dark.

Has the art brush filled money bags to bursting and depicted jewels and other worldly treasures, focussing attention on them and using reason to consider the nature of such things, it teaches the mind as a consequence that

They who gawk at shining gold

And search for their rest in money,

Will ever find restlessness which torments them

Both in the eager scraping together

As in the possession of their wish;

But though the same yields neither pleasure

Nor rest, but restlessness after the labour,

It still remains the target of men.

It was thus before and remains to this day,

The god of coinage is ever worshipped.

It is certain, says Isodorus, that the edifying finds of human intellect spring from a good upbringing or out of natural disposition. And where a commendable spirit guides the brush, the depiction is edifying. For this LEONARD van ORLEY is also praised, as well as one WALTHER DAMERY of Liege, who mainly depicted

Page 289

emblematic scenes and moral images with their art brush that can raise an attentive mind to virtue.

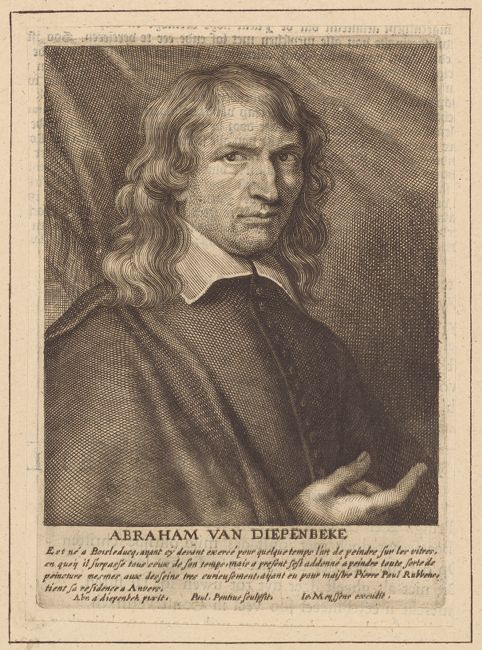

ABRAHAM van DIEPENBEECK was born in Den Bosch. I do not know when he was born, but he was still alive in 1662. From his youth on and from then on spent most of his life on the treatment of transparent objects, that is glass, which he was able to decorate so artfully with figural work and histories with his brush that he was seen in his time as the best master in that art. Cornelis de Bie says:

In the Netherlands he was called the most robust spirit:

Was tender in painting, very loose and well-rounded,

Also firmly drawn, and his colours wonderfully strong.

He learned the art of painting with the great Peter Paul Rubens, and being of a noble spirit, did not take satisfaction with the praise that he garnered with glass painting, but also took up painting pictures. But added to this there was a second reason (which we found in the Beschryving der Stad Gouda), to wit (after the glass is painted, it must be baked in an oven) that this repeatedly failed while he was in Italy. That is why he cursed the pursuit and turned entirely to panel painting, at which he succeeded so well that the prince of Dutch poets, Joost van den Vondel, honoured his portrait, painted by himself [1], with this verse:

1

Paulus Pontius (I) after Abraham van Diepenbeeck published by Joannes Meyssens

Portrait of Abraham van Diepenbeeck (1596-1675), c. 1649

The Hague, RKD – Netherlands Institute for Art History