Volume 1, page 260-269

Page 260

he preferred to keep the incomplete portrait for himself sooner than put the brush to it to please them, which also came to pass. And so the said piece served afterward as a partition for his students.

Nevertheless there are still many of his artworks that are thoroughly painted and executed to be seen in the most important art cabinets, although many of them were bought up at a high price some years ago and carried off to Italy and France.

And I have observed that in his early period he had more patience with the detailed execution of his artworks than subsequently. Among several examples, this is particularly to be seen in the piece known as Saint Peter's ship, which hung for many years in the cabinet of Mister Jan Jacobz. Hinlopen, formerly bailiff and burgomaster of Amsterdam [1]. For the effect of the figures and the facial features in it have been as elaborately expressed according to the nature of the situation as is possible and further painted in greater detail than one is used to seeing from him. Also in the same place is a piece in which Haman is guest of Esther and Ahasuerus, painted by Rembrandt [2], of which the poet Jan Vos, as a sensible connoisseur, thus expresses its content as well as the emotions that are to be observed in it:

Here one sees Haman dining with Ahasuerus and Esther.

But it is in vain, his breast is filled with regret and pain.

He bites into Esther's food, but deeper into her heart.

The King is possessed by wrath and frenzy.

1

Rembrandt

Christ in the storm on the Sea of Galilee, dated 1633

Boston (Massachusetts), Isabella Stewart Gardner Museum, inv./cat.nr. P21S24

2

Rembrandt

The second meal of Ahasuerus and Haman with Esther (Esther 7:1-7), dated 1660

Moscow, Pushkin Museum, inv./cat.nr. 297

Page 261

The anger of a ruler is frightening when it rages.

He who threatened all men, is by a woman surprised.

Thus one falls from the peak into adversity's abyss.

The revenge that approaches slowly wields the most severe of rods.

Thus is also the small piece entitled The Woman Taken in Adultery [3], with Mister and Master of Laws Willem Six, ex-alderman of the City of Amsterdam. It is painted in grisaille like the little piece of the preaching of John the Baptist [4], marvellous because of the natural depiction of the attentive expressions and varying dress, to be seen in Amsterdam with Mister Postmaster Jan Six. This has me decide firmly that he gave this aspect his special attention and paid less attention to the rest. I am all the more convinced of this because a few of his students have explained to me that he sometimes sketched a face in no fewer than ten different ways before he committed it to panel and could also spend a day or two setting up a turban to his satisfaction. But as far as the nude is concerned, he did not make as many preparations but most of the time rushed through it sloppily. If one sees a good hand by him it is rare, as he obscures these in shadow, especially in his portraits. Or it must be the hand of an old wrinkled biddy. And with respect to his nude women, the most delightful subjects for the artist's brush, on which all great masters from ancient times on lavished all their effort, they are (as the saying

3

Rembrandt

Christ and the woman taken in adultery, dated 1644

London (England), National Gallery (London), inv./cat.nr. NG45

4

Rembrandt

John the Baptist preaching, 1634/1635

Berlin (city, Germany), Gemäldegalerie (Staatliche Museen zu Berlin), inv./cat.nr. 828 K

Page 262

goes) too sorry to sing, or play, about. For they are usually displays that must disgust people and make them wonder that a man of such great talent and spirit was so perverse in his preferences.

It will not rue readers, especially those inclined to know art according to reason and the most certain foundations, be it in order to apply them or to be able to discuss them so that they know and understand the basics of the different concepts that great masters have had in the practice of this art and which they put forward as a fundamental law, that I for once compare two great lights in the art of painting with regard to their approach to practice and that I then frankly pronounce my judgement together with that of Karel van Mander. He said that Michelangelo was wont to say: That all painting, no matter what it was, or by whom it was made, was only child's play and trivial work if everything is not painted after life, and that there can be nothing good or better than to follow nature; consequently he never did a single stroke without placing nature in front of him Etc. Our great master Rembrandt was also of this opinion, taking as his fundamental rule nothing but imitation of nature, and everything that was done outside of this was suspect to him. What does Van Mander conclude concerning this? This: That it is not a bad way to arrive at a good destination, for to paint after drawings (even if these are done purely after life) is not as certain as having nature in front of oneself and to follow nature in all of her different colours. Yet one is still obliged to develop one's understanding

Page 263

so far that one can distinguish the most beautiful life from the beautiful and is able to choose it. Here is the crux: To be able to choose the most beautiful out of the beautiful, which we shall try to explain more concretely.

We should gladly like to affirm that painting after life is necessary and good, but that this cannot be elevated to such a general principle that solely to follow life would be the way to reach perfection in art, for then it would necessarily follow that those who were most inclined to painting after life would be the best masters of art, which is not generally the case, but on the contrary is found by many to be untrue. For I have come across paintings in which everything was painted with great application and with the utmost detail after life, and yet there was neither harmony, nor recession, nor composition, nor drawing in it. And still others that were not so precisely after life, but where the spirit of the artist came out better, that were sound in all aspects of art, and could pass for good and honest paintings.

In addition there are countless things and subjects that are each in turn employed in painting for which life is inapplicable, such as, for instance, flying, tumbling, jumping, or walking figures, whose movement and action change every instant, so that the painter can't make use of them in this way. However, there have been in all ages masters who to their great credit knew how to paint such subjects marvellously

Page 264

according to art, without the aid of life. Yes, how would those who painted those great fixed pieces 20 or 30 feet from the ground, on scaffolds and supports have made use of life? Consequently they had to use their fixed conceptions and cartoons as subjects in order to paint after them. Once more.

Just imagine, one must show joy, happiness, sadness, fright, anger, amazement, scorn and so forth, that is, the manifold manifestations of the soul, through fixed and recognizable facial expressions. How should people deal with that? You could easily answer: one can command the living model to laugh, to scream etc. and in this way make use of life. Yes, but then it is pretty much crying to laugh at and to look around sadly to see if one were being mocked, because the body cannot have the required sensation without the passion of the soul, and therefore the expressions are unnatural, as they do not animate the features by the power of the spirit, but by force. As consequence perfection cannot be achieved in art through the imitation of life in this respect, but the work must necessarily remain deficient because its object lacks what is required for a work of art.

Also many emotions do not last for long, for the expressions instantly change appearances with the least shift in emotion, so that there is hardly time for sketching, leave alone painting, and consequently no other way can be conceived by which the practitioner of art can profit in this respect than by a single perception and fixed conception,

Page 265

or one must avail oneself of the intellect of those who through concrete rules and features of art have communicated to the world by means of prints each specific emotion as direction for avid scholars. Similarly there is that praiseworthy book: Discours Academiques, which was drawn up by the masters of the Royal Academy in Paris for Monsieur Colbert, after whose example we have also drafted up a sample of this method, using other borrowed subjects, and included it in the second volume of Philaléthes' letters.

Someone will probably respond, Rembrandt has certainly understood the representation of particular expressions and is praised for it; has he not done this according to a concrete basis? I answer yes: but on a basis that I cannot recommend as an example for general instruction in that by means of a wonderfully concrete conception, he knew how to imprint the emotions in that instant when they appeared on the faces of the subjects and to make use of them. This is only a rare natural capacity which does not require our lessons, our instruction serving only to train those who do not have this gift by proven means in order to become competent in this.

To clarify this business of the use of life a little further, I say I. It must be preceded by a concrete conception of the entire subject of what one wants to achieve, of which one cannot form a perfect conception unless one knows and understands what is required in a work of art that one proposes to do: specifically the arrangement of figures

Page 266

and their effective interaction, so as to be able to rearrange the model before one gets around to painting after life. Without this the entire work stands on loose screws. I shall briefly give you an example of a lower order. In order to put this to the test, I say: It is necessary that one draw after life in the Academie. Everyone will grant me this and willingly add that from life, one learns to understand life. It seems well said, reader, but do not judge too hastily, for most of the young students here in Holland who draw from the nude, draw without benefiting from it because they lack a certain judgement and knowledge that must be there in advance for them to enjoy the fruit of drawing after life. This comprises I. That they are not accustomed enough to copying fine Italian prints and drawings. II. That they do not apply themselves enough to drawing after plaster, formed from the finest antique sculpture, as well as sketches by the most renowned masters, to the degree that they learn to distinguish the beautiful from the common. III. That they do not understand human anatomy fundamentally, that is they do not know all the muscles in the human body in order to know how one or the other muscle alters in form through movement and extension of arms or legs, that a contraction means a swelling, whether a stretching is transformed into an oblong or angular form. The saying: One must venture on the ice properly shod applies here. For without these preparations there cannot be a single footstep of progress in art, or the achievement of the purpose one has in drawing after the nude. Do you want to know the reason why?

Page 267

Human bodies differ from one another in this, that muscles show themselves much more distinctly in one body than in another. What will someone who is inexperienced in anatomy make of it when the muscles present themselves in soft or indistinct gradations? Such a person will not know what he sees, and also put down on paper that of which he does not know what it is, or why it is that way, and consequently as uncertainly as if it were being dreamed. On the other hand, the person who understands and knows the position of the muscles in motion, and their form, knows how to make use of indistinct observations. Charles Le Brun, supervisor of the King's Academy in France, has brought this kind of instruction into practice, and produced many fine spirits and famous painters from it.

Rembrandt (to put an end to this plea) would not bind himself to the rules of others, and even less follow the illustrious examples of those who by choosing the beautiful have forged eternal fame for themselves, but satisfied himself with following life as it presented itself to him, without making choices

Page 268

concerning it. Which is why the gentle poet Andries Pels says of him most acutely on p. 36 of his Gebruik én misbruik van het toneel,

When he would paint a naked woman, as sometimes occurred,

He did not turn to a Greek Venus as model,

But sooner a washer woman or a turf cutter from a shed;

Calling his error the imitation of nature,

Everything else is idle decoration. Flaccid breasts,

Distorted hands, yes the pinches of the laces,

Of the corset on the belly, of the garters on the leg,

It all had to be followed, or nature was not satisfied,

At least his, which tolerated neither rules, nor any reason

Of proportion in a body's members.

I laud this honesty in Pels and appeal to the reader to interpret my candid judgement positively, not as arising out of hatred of this man's work, but to compare the different conceptions and varying practices of art with each other and to urge the studious to emulate what is most praiseworthy. For aside from this I must say along with the aforementioned poet:

What a loss it is for art, that so outstanding a hand,

Did not make better use of its bestowed talent

Who would have surpassed him in painting?

Oh well! the greater the spirit, the wilder it will run,

If it binds itself to no principle, or leash of rules.

But seeks to understand everything on its own!

Page 269

Still to pass over all this, his art was respected and sought after so much in his time that (as the saying goes) one had to beg him as well as pay him. For many years he was so busy painting that people had to wait a long time for their pieces, notwithstanding that he proceeded handily with his work, especially in his late period, when, seen from up close, it looked as if it had been smeared on with a bricklayer's trowel. Wherefore he pulled people back if they came up to his studio and looked at his work up close, saying: the smell of the paint would annoy you. It has also been attested that he once painted a portrait, on which the paint lay so thick that one could lift the painting up from the ground by the nose. So one also sees jewels and pearls, or torso decorations and turbans painted by him in such relief as if they were sculpted, by which manner of handling his pieces project powerfully even from a great distance.

Amongst a multitude of laudable portraits that he has made, there was one with Mister Jan van Beuningen which he had painted after his own features, which was worked out so skilfully and forcefully, that the most powerful brushwork of Van Dyck and Rubens could not match it, yes the head seemed to project from the piece to address the spectators. No less is the work that hangs in the Gallery of the Grand Duke of Florence [5] next to the portraits of Philips Koninck [6], Frans van Mieris I [7], Gerard Dou [8], Bartholomeus van der Helst [9], Ferdinand Voet [10]

5

Rembrandt

Self Portrait, c. 1669

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 69.232

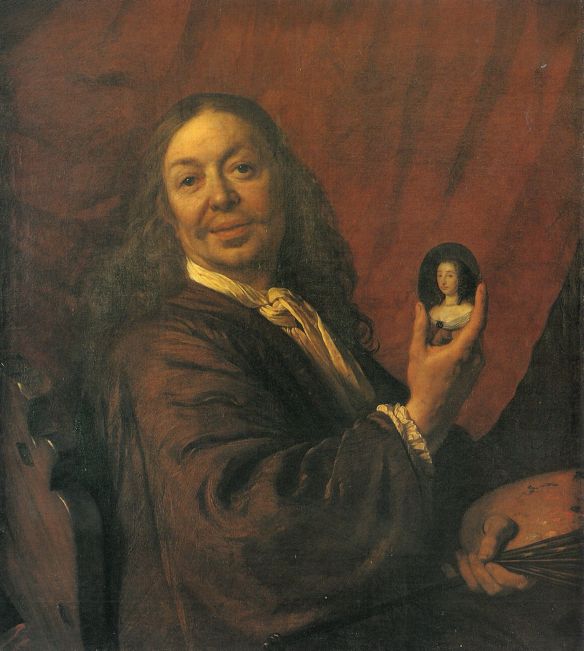

6

Philips Koninck

Self-portrait of Philips Koninck (1619-1688), 1667?

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 1890, no. 1885

7

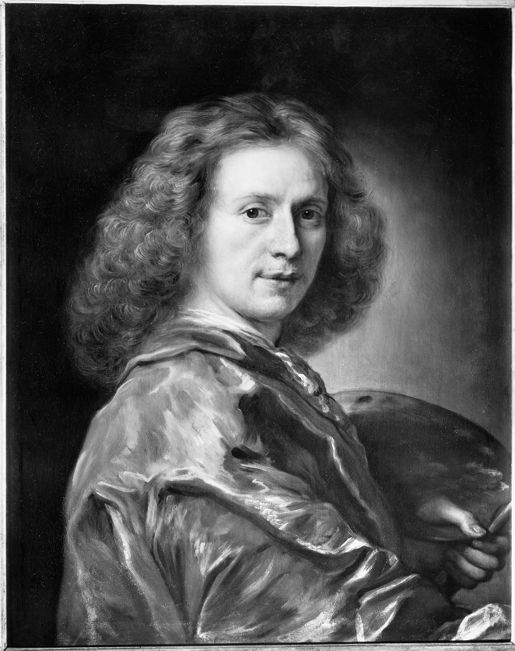

Frans van Mieris (I)

Self-portrait of Frans van Mieris I (1635-1681), c. 1677

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 1876

8

Gerard Dou

Self-portrait, dated 1658

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 1882; A311 (Berti/Caneva 1979)

9

Bartholomeus van der Helst

Self portrait of Bartholomeus van der Helst (1613-1670), dated 1667

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 1890, no. 1683

10

Ferdinand Voet

Selfportrait, 1670s

Florence, Galleria degli Uffizi, inv./cat.nr. 476 (cat. 1910)