Volume 1, page 180-189

Page 180

Of birds, from all over, which happy at the meeting

Greet that son of the Sun with clucking and song.

And truly, many have always viewed his work with admiration, be it out of love of art or desire for learning. Yes, experience has shown us that when any of his important works come to light and opportunity is arranged to come and see them (as with the pieces that were brought from 't Loo to the Gentlemen's Inn in the year 1713), people are attracted in the same way that mosquitoes swarm to light. And if people owe respect to art, it is deserved by that of Anthony van Dyck, in which one can discern not only drawing that accords with the rules of art corresponding to life, but that could also compete with life at its most beautiful, but also power and clarity in the blending of paints, so that nature, should she care to have herself inspected next to this art, would be seen to blush with shame. At the sale of the 26th of July of the aforementioned year, the art lovers showed the world how much esteem they had for van Dyck's art. For one work 7 feet long and 10 feet wide (in which Mary, Joseph and Jesus, as well as some dancing cherubs were depicted) was sold for 12,050 guilders [1].

Having had the opportunity to view a great many of his artful portraits from nearby, I have often been amazed about the singular handling, which is very well done but brushed in a sloppy way.

To continue with Van Dyck’s biography, I profess firmly to believe that the

1

Anthony van Dyck

Rest on the flight into Egypt: the Madonna with the partridges, c. 1630

Sint-Petersburg, Hermitage, inv./cat.nr. 539

Page 181

writer of the city of Gouda, mentioned above, recorded the matter of his father faithfully and truthfully, and I have had no intention thereby to mislead the descendants, since he could not have known in advance that this material would ever be used to serve as proof of or for the honour of these descendents, as it does now. Because the entire story that people have made up (that Peter Paul Rubens picked up Van Dyck from the street and raised him) falls apart.

One matter serves as a hindrance for me, which is the difference I find amongst writers concerning his birth. Who can be more correct? And yet we wished to be certain in our annotations. Cornelis de Bie gives the year of his birth both in his book and under his portrait. But Louis Moréri, in his general dictionary, says that he was born in the year 1598. Now I cannot take this for a printing error, as he also moves the year of death earlier, but Moréri goes agains all testimony in this, and we will follow the greater majority. But I find with mentioned writer matters that occur in his life which are also described by others but booked much more precisely and with greater attentiveness by him, such as, among other things, who was his first master in art and that he had a woman to whom he was married, and of what family, since others have argued off the top of their heads (as people usually say) and have questioned whether he really had a true wife, as well as special information concerning his estate and more

Page 182

particularities, of which we will make use in their place. It all gives me assurance that I may follow him in this. But when he claims that Hendrick van Balen was Van Dyck’s first instructor in art, he would not have said that if he had known that his father [= Frans van Dyck] was an art practitioner but have reserved that honour for his father, while it is evident that he would have taught his son from his youth on according to his receptivity.

And not only was the father of Van Dyck a practitioner of art, but his mother [= Maria Cuypers] was also a famous artist with the embroidery needle. Amongst her stitched works is praised a chimney-hanging in which, using all sorts of colours of silk, she had depicted the history of Susanna, the figures firm in outline, and the blending of colours according to the nature of each item, as also the hem of the rug with loose vines so inventively interwoven that this one needlework alone sufficed to praise her intellect. It is further told that she worked on it with particular diligence at the time that she was pregnant with Anthony van Dyck (whose portrait appears opposite).

Whether Van Dyck was instructed by Van Balen before he came to Rubens, I do not know with certainty, but that he was a student of Rubens is known to all, as well as that he progressed so far in art under his guidance that he put him to working on his best works. While he was still with his master he painted his portrait [2], that of his wife [3] and of various others as well as some

2

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Peter Paul Rubens (1577-1640), c. 1628-1632

Boughton House (Northamptonshire), Bowhill House (estate), Montagu House (Bloomsbury), private collection Duke of Buccleuch and Queensberry

3

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Isabella Brant (1591-1626) in the garden of Rubens's house in Antwerp, 1621

Washington (D.C.), National Gallery of Art (Washington)

Page 183

pieces with various figures by which he secured more fame than money because Rubens, admired by all the great, was (as I have said more often) too far ahead in all advantages to be able to compete with him.

The first two pieces in which he showed his ability in art after he had left his master were the capture Christ in the court [3] and when the crown of thorns is placed on his head by Roman soldiers [4].

At this time Italy was in full flower and appeared to tempt everyone to a race in art for the crown of immortality. Yes, people spoke of Rome no differently than of the Greeks or Athens, as if the goddess of art had established her seat there, which is why one daily saw artists flow there from all places, so that our Van Dyck also got wanderlust in his head, to which his master also encouraged and pushed him especially to go see the art of Titian in Rome and Venice. But it is said that he found this advice from Rubens suspicious, as if he only gave it to get him away from home base, so that the rays of his rising sun would not cloud over his own light. That may be as it may. Various examples have shown us that Rubens sincerely loved Van Dyck.

The journey was on, however, and Mister Giovan Battista Nani was one of those who accompanied him on the way to Rome. But the journey did not take as long as they must have imagined because the plague increased markedly in various Italian cities. However, he was there long enough that when

3

Anthony van Dyck

The arrest of Christ and the kiss of Judas, c. 1617-1620

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. 1477

4

Anthony van Dyck

The mocking of Christ, c. 1618

Madrid (city, Spain), Museo Nacional del Prado, inv./cat.nr. 1474

Page 184

he had returned, one could see from his treatment of the nude that he had looked closely at the art of the great Titian, because from that time on one saw more of a mother of pearl-like tenderness in his nudes than before

After he had remained in France for a long time without gaining much profit, he returned to Antwerp, where he was welcomed, especially by his teacher Rubens, who (if the story should be true) offered him his daughter under sufficiently understandable circumstances, which he declined in a polite fashion under the pretence that he was planning once more to resume his Roman journey. But (as is often said in such cases) this was not the true message, but this: That he had a general love for the feminine figure and could not limit his inclination to a single object: although he was later married in England.

The first large piece that he made after he had returned from his journey was the high altarpiece of the monastery of the Augustinians in Antwerp, which made his name known [5-6]. But he could easily carry the gold that he put in his purse for it, since this brotherhood, which loved having a great deal more than giving, found a fair amount to complain about, and that about the most important part of the work, to wit the figure of St. Augustine, claiming that it looked as if, being drunk, it was falling backward, since Van Dyck had depicted the amazement at the contemplation of the heavenly vision with that figure.

5

Anthony van Dyck

Saint Augustine contemplating the Trinity, documented 1628

New Haven (Connecticut), Yale University Art Gallery, inv./cat.nr. 1959.15.26

6

Anthony van Dyck

The ectasy of Saints Augustine and Monica, 1628

Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen

Page 185

Not much later he was summoned by Frederik Hendrik, Prince of Orange, to paint his portrait and that of the princess [= Amalia van Solms-Braunfels] and son [= Willem II] [7-9], which he did to their great satisfaction. Returned to Antwerp he made an altarpiece for the Capuchin monks in Dendermonde [10], which turned out so well that it was estimated to be one of his best works.

Next followed a piece for the Franciscans which depicted a dead Christ in the lap of Mary [11]. These three works, each painted in the most beautiful way possible, announced the fame of their maker. Even if he had not left the world any more samples of his art, it would have been enough to see that he was the phoenix amongst the painters of that century. At once many opportunities to paint portraits flowed his way, which succeeded so wonderfully well that it seemed as if he was born for this, so that that the highest people of eminence approached him. Among these was Isabella Clara Eugenia, Duchess of Brabant etc., painted by him in nun’s habit, about which Jan Vos made this verse.

Thus one sees Isabella casting off the courtly show.

She gives up purple for the nun’s habit.

Her head requires no crown but that of peace olives.

She prefers the palm branch over the golden pearl staff.

The tips of her virtue go higher than the clouds.

The virtue of the great serve as beacon for all the people.

In the meantime he became known to the English by the painting of his more than artful portraits. And it did not take long before the knight Kenelm Digby

7

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Frederik Hendrik van Oranje-Nassau (1584-1647), c. 1632

Baltimore (Maryland), Baltimore Museum of Art, inv./cat.nr. 1938.217

8

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Amalia van Solms-Braunfels, Princess of Orange (1602-1675), c. 1630

Private collection

9

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Willem II van Oranje-Nassau (1626-1650) as a child, c. 1628-1632

Schloss Mosigkau, Museum Schloss Mosigkau, inv./cat.nr. 13

10

Anthony van Dyck

The adoration of the Shepherds, 1630-1631

Dendermonde, Onze-Lieve-Vrouwekerk (Dendermonde)

11

Anthony van Dyck

Lamentation over the dead Christ by his relatives and friends, c. 1634

Antwerp, Koninklijk Museum voor Schone Kunsten Antwerpen, inv./cat.nr. 404

Page 186

requested him to ship to England. This individual brought him to King Charles I, whom he painted several times, as also Queen Henrietta Maria de Bourbon and the princes Charles II and James II, as well as most of the lords and great of England, which made his purse swell fatter than before. In addition the king honoured him with a knighthood and a gold chain with the king’s portrait surrounded by diamonds and an annual salary, which mightily spurred on his diligence and desire. But it is to be lamented that many of his best works that he made for the king have been dispersed or burned.

It is true, his diligence and desire increased as his purse swelled, but it did not take long before he was so enchanted and misled by the fancy talk of a cheat who passed himself off as alchemist or gold maker (as these people still are and remain seekers of gold), that he had a laboratory erected and suffered thousands in expenses without any profitable outcome except that he learned not to undertake such a venture again, and saw clearly that painting was the best and surest gold- mine for him.

He who was now daily at the court and saw so many a pleasing object, let his eye fall on the most beautiful, whom he wed (because he could not possess her in any other way but by marriage) with the approval of the King. This was one of the most beautiful and prominent ladies of the court [= Maria Ruthven] and of an old and noble family from Scotland, daughter of Lord Ruten, Earl of Gowrie. But he did not take anything as dowry but her beauty and nobility.

Page 187

I could not have been more amazed when, being in England, I saw so many portraits marked with the same year, from which I had to conclude that he had an unusually deft brush. Most of the courtiers and great of that king and in addition their spouses, as well as ladies of state were painted by him at that time, of which several have been issued in print.

At Winchendon, the country estate of Lord Thomas Wharthon, 1st Marquess of Wharton [= son of Philip Wharton, 4th Baron Wharton] [12], I saw 32 portraits, of which 14 full-length, in one room, each individually painted by him at his most sublime and ingenious, especially the portraits of women. About them I have observed that he must have had a perfectly beautiful model for the painting of the hands, as well that he used a certain number of selected comely bends and clasps of hands throughout his work and thus used the same hands in various portraits. And while I write about his beautiful and artfully formed hands, a sentence, a witty answer which he shot at the queen comes to mind. The latter then having repeatedly been portrayed by his brush, asked him why he had flattered her hands more than features, to which he answered: Because I expect my reward from them. But it is to be regretted that such a beacon of art was so untimely torn away by death. But what shall I say? He had (as I was told in England by several reliable people) singed himself on the flame of Cupid's torch, and to cool that fire

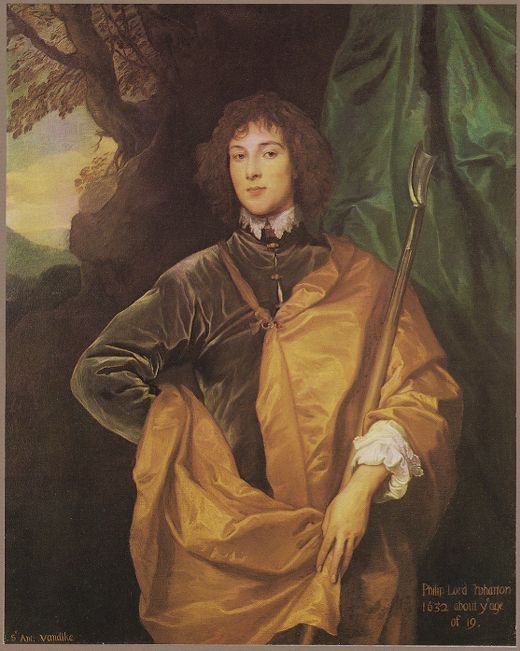

11

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Philip Wharton, 4th Baron Wharton (1613–1696), dated 1632

Washington (D.C.), National Gallery of Art (Washington), inv./cat.nr. 1937.1.50

Page 188

the physicians extinguished the fire of his life, so that he was not to be warmed. King Charles, who had great affection for him, ordered his doctor not to spare any expense with him but to set in motion anything that could help him, with the promise to give him 300 Guineas for his recovery. This doctor had a cow killed, pulling out the entrails in all haste and (leaving but a small opening for him to breathe) sewed him in naked to warm his blood and revive his spirits. But it was in vain. He lived for only a short while and died in the year 1641. He was buried in the church of St. Paul in London.

All those whom one wishes to live long because they are useful will often die early, and those who are good for nothing live the longest, says Baltasar Gracián.

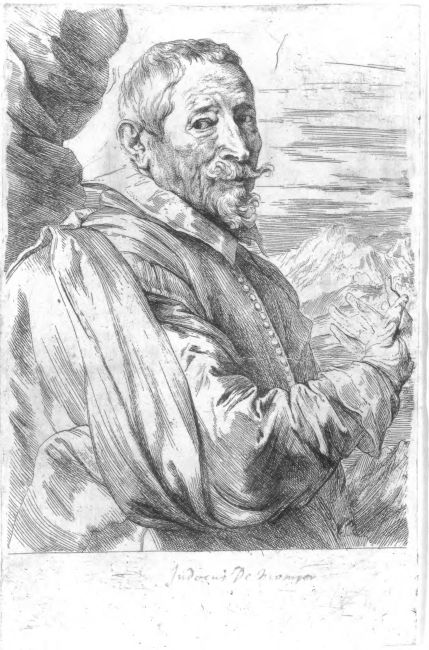

We have placed JOOS de MOMPER, like other of his fellow artists and contemporaries for whom the beginning and end of their lives are unknown to us, after Van Dyck, to whom they remain indebted because he has perpetuated their remembrances for the centuries with his phoenix brush. On p. 208 of his book [= Het Schilder-Boeck] Karel van Mander commemorates De Momper thus: There still is in Antwerp one Joos de Momper, who excels in landscape, having a lively handling. His brushworks, known to all painters, indicate that he was a commendable master at that time. His portrait was etched in copper by the great Van Dyck with his own hand [13].

So also the Hague portrait painter JAN van RAVESTEYN, and CORNELIS de VOS

13

Anthony van Dyck

Portrait of Joos de Momper II (1564-1635), c. 1633

Whereabouts unknown

Page 189

from Hulst, whose firm features show that he must have had a shrewd intellect.

ADAM de COSTER.

DANIEL MYTENS, who according to Cornelis de Bie was a Dutchman and painted many important people with success, since he had a lush and flattering way of painting.

ARTUS WOLFFORT of Antwerp, who is not only famous by painting moral pictures but also fables and comical works, and

THEODOOR van LOON of Louvain, who showed satisfactorily by the handling of his bold figures that he had seen Rome. With this painter we will close this century.

Thus the years and also the years of men go by, and those who showed themselves alive in the theatre, one after another, now lie buried behind the stage curtain. With the writing of this word I am most certainly reminded that my reflections have long been pregnant concerning the burial of dead corpses and the various treatments that the ancients used in connection with this, seeing that painters have often made mistakes concerning this though ignorance; and even more with respect to the old customs of the Jews than of the heathens. For since the most important corpses of the Greeks and Romans were burned with great pomp and brought with them much fuss, so their contemporary writers, especially